Helpful books and resources

This section includes comments on books and resources that may be found helpful.

Arguments in Action

Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide

Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide, by

Tracy Bowell and Gary Kemp,

This is the first of the ‘helpful textbooks’ listed in the most recent Course Specification. Indeed, it should prove helpful in many ways. It is written clearly, has a simple introduction to argument diagrams, and has lots of useful exercises.

However, including this text in the list of helpful textbooks raises some interesting questions for both centres and the exam team. The book frequently uses different terminology to that traditionally used in Higher Philosophy. It probably doesn’t matter that it refers to argument trees rather than argument diagrams and, although once in the book it does refer to strong and weak inductive arguments, it generally talks about inductive force rather than inductive strength. It refers to 'extended arguments' rather than serial or complex arguments. (It is worth noting that only serial arguments are mentioned in the mandatory content but complex arguments are mentioned in the appendix on argument diagrams and this may impact on what can legitimately be asked in an exam question.) It also refers to connecting premises where the course has traditionally spoken of hidden or suppressed premises even though these are not specified in the current course.

It may be that none of these will prove problematic but it would be reassuring to know that if a class was using this text and ended up using this terminology it would be recognised by the markers.

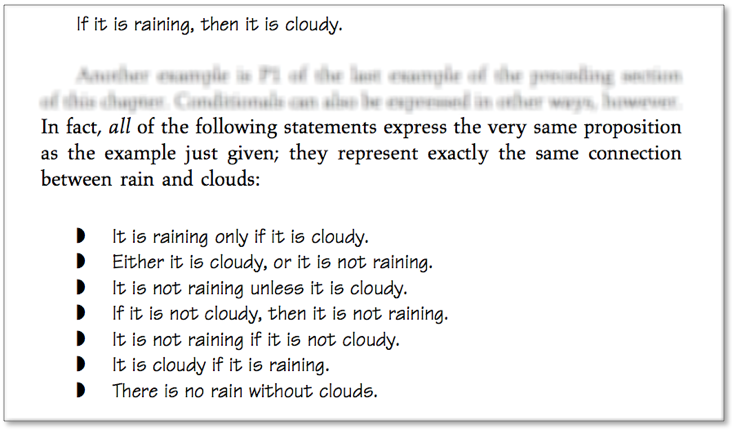

On other occasions there is the possibility of confusion. This book emerges from a background in formal logic so, for example, it makes a point of saying that an argument is ‘a system of propositions’. In some areas of philosophy it is deemed important to distinguish between sentences, statements, and propositions. In this book ‘statement' doesn’t make it into the glossary but it is clear that ‘statement’ and ‘proposition’ are not being treated as synonyms (which is implied by the National 5 glossary). In particular, the authors say a single proposition can be expressed by different statements.

Elsewhere they write

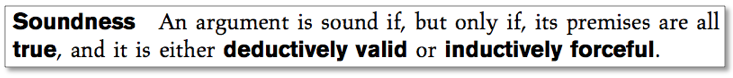

“...our primary task in this chapter and the next is to explain the basic logical concepts in terms of which [argument] assessment is carried out – validity, soundness and inductive force.”

The problem here is twofold. Firstly, this is different to the process of argument assessment now required by the course. Secondly, although the term ‘sound’ is not specified it is reasonable to assume that it will continue to be used. It is just that in this book it is applied to inductive arguments as well as deductive arguments.

Another issue is that this book has a section on relevance but is using the term differently to the way it is used in the Higher Course. In the course relevance is to do with evaluating an argument but in this book it is used for weeding out material prior to reconstructing an argument.

Finally, the book has a very precise definition of what is meant by an inductively forceful argument. It means an argument where the conditional probability of the conclusion relative to the premises is greater than one-half, but less than 1. It is important to note that this is different to ordinary usage where when we say a statement is probably true we usually mean the chances of it being true are substantially greater than a probability of 50% (This is why Bickenbach and Davies can speak about cogent but weak arguments.)