Helpful books and resources

| Stránky: | Higher Philosophy |

| Kurz: | Higher Philosophy: Some notes and observations. |

| Kniha: | Helpful books and resources |

| Vytiskl(a): | Gæst |

| Datum: | pondělí, 21. dubna 2025, 03.10 |

Popis

This section includes comments on books and resources that may be found helpful.

General resources.

Resources that may be helpful for more than one area of the course.

Understanding Philosophy for AS Level

Understanding Philosophy for AS Level, by

Christopher Hamilton

This school-level textbook, which was published in 2003 for the AS level course, has some very useful chapters on utilitarianism, Kantian ethics and Descartes. It is particularly helpful in its evaluative/discussion material. Of the three, the chapter on Kantian ethics is probably the strongest. With the exception of an early sentence, which is at best confusing, it explains contradiction in the will in a way that students will find very helpful. It’s chapter on utilitarianism goes beyond what is required for the Higher course but has some useful discussion of criticisms. It is again at its strongest when discussing various criticisms of Descartes. Its explanation of the trademark argument, whilst maybe not the best, will no doubt help those who struggle with this part of the text. The discussion of the dreaming argument and the cogito is also very helpful.

The book is less helpful with its general approach to Meditation One. As so often happens, it is used as a jumping off point for a discussion of epistemology and this skews its discussion of the text. At one point Hamilton emphasises that “Descartes is not claiming that he will disbelieve everything that is even capable of being doubted...he will neither believe nor disbelieve, but withhold his assent.” This sits very uneasily with the text where Descartes says, “I think it will be a good plan to turn my will in completely the opposite direction and deceive myself, by pretending for a time that these former opinions are utterly false and imaginary... I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colors, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams... I shall consider myself as not having hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as falsely believing that I have all these things...”

This is no doubt related to the way Hamilton glides over why Descartes introduces the malicious demon by simply saying it was “to make the hypothesis of the deceiving God more vivid.”

Video Series: The Examined Life

This video series is now twenty years old and was aimed at college students but it is still useful. The episodes can be demanding for Higher pupils but if they are given questions to keep them on task that helps.

DVDs of the series sometimes become available on places such as ebay.

A standard web search will usually find some of them as well but, as with much of the material on the web, I wouldn't vouch for it being there legally.

The four episodes that might be particularly useful are:

| Is reason the source of knowledge? | questions | |

| Does Knowledge Depend on Experience? | questions | |

| Can Rules Define Morality? | questions | |

| Does the end justify the means? | questions |

The episode, Moral Dilemmas ... Can Ethics Help?

has been made legally available and will give a sense of the series.

Arguments in Action

There are a lot of books and other resources that address the topics covered in the Arguments in Action section of the course. However, they are perhaps more diverse and varied than resources for other parts of the course. Books can differ even in their definitions of such well-established terms as ‘deductive’, ‘inductive’, ‘valid’, ‘sound’, etc. Sometimes these definitions can be inconsistent and contradictory. It is vital, therefore, that teachers use the mandatory documents to ensure they are using terminology and definitions that are approved for the course. Extra guidance can be gained by consulting recent marking instructions but caution should be used if using older marking instructions particularly if the course has changed. It should also be remembered that marking instructions are working documents produced each year and may have been amended for pragmatic reasons at the marking event in the light of candidate responses. Marking instructions are not mandatory documents and may have been superseded by later mandatory clarifications.

Argument diagrams are presented in different ways by different authors and some of the online material is closely aligned with particular software packages. The SQA guidance on argument diagrams allows for some variety and information in books and other resources should be checked against this guidance.

The Higher Course approach to argument evaluation is reasonably standard in the field of informal logic but some books on informal logic also use ‘argumentation schemes’. This goes beyond what is required of Higher candidates.

There is a lot of material available on fallacies but they are sometimes described and classified in different ways. Again, it is necessary to refer to the mandatory information issued by the SQA to ensure the material is being delivered in an appropriate way.

A Practical Study of Argument

A Practical Study of Argument, by

Trudy Govier

If you were only going to buy one book to help with Arguments in Action this is the one I would be recommending. It does have some material on argument diagrams but where it really excels is with the evaluation of arguments using the acceptability, relevance and sufficiency criteria. Govier prefers the term ‘good grounds’ to sufficiency but it means the same thing. There is much more here than is needed by someone following the Higher course but its clarity and large number of examples makes it an invaluable resource.

This book is one of those recommended in the Sept 2018 Course Specification.

It is worth noting that it uses slightly different definitions for inductive argument and cogent compared to those used previously in Higher Philosophy.

Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide

Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide, by

Tracy Bowell and Gary Kemp,

This is the first of the ‘helpful textbooks’ listed in the most recent Course Specification. Indeed, it should prove helpful in many ways. It is written clearly, has a simple introduction to argument diagrams, and has lots of useful exercises.

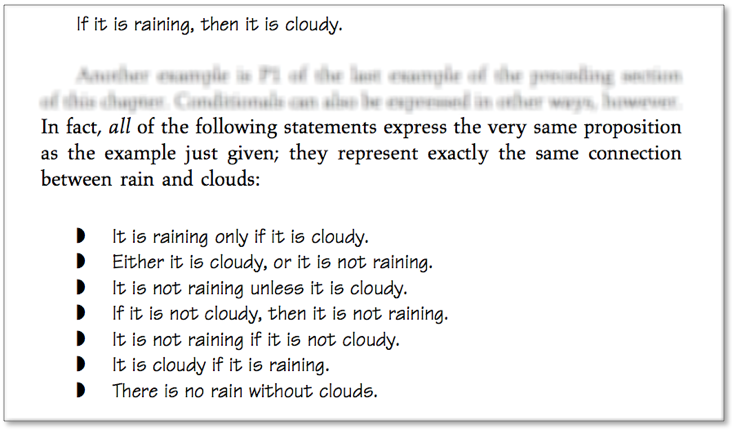

However, including this text in the list of helpful textbooks raises some interesting questions for both centres and the exam team. The book frequently uses different terminology to that traditionally used in Higher Philosophy. It probably doesn’t matter that it refers to argument trees rather than argument diagrams and, although once in the book it does refer to strong and weak inductive arguments, it generally talks about inductive force rather than inductive strength. It refers to 'extended arguments' rather than serial or complex arguments. (It is worth noting that only serial arguments are mentioned in the mandatory content but complex arguments are mentioned in the appendix on argument diagrams and this may impact on what can legitimately be asked in an exam question.) It also refers to connecting premises where the course has traditionally spoken of hidden or suppressed premises even though these are not specified in the current course.

It may be that none of these will prove problematic but it would be reassuring to know that if a class was using this text and ended up using this terminology it would be recognised by the markers.

On other occasions there is the possibility of confusion. This book emerges from a background in formal logic so, for example, it makes a point of saying that an argument is ‘a system of propositions’. In some areas of philosophy it is deemed important to distinguish between sentences, statements, and propositions. In this book ‘statement' doesn’t make it into the glossary but it is clear that ‘statement’ and ‘proposition’ are not being treated as synonyms (which is implied by the National 5 glossary). In particular, the authors say a single proposition can be expressed by different statements.

Elsewhere they write

“...our primary task in this chapter and the next is to explain the basic logical concepts in terms of which [argument] assessment is carried out – validity, soundness and inductive force.”

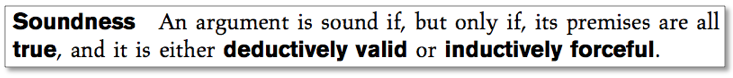

The problem here is twofold. Firstly, this is different to the process of argument assessment now required by the course. Secondly, although the term ‘sound’ is not specified it is reasonable to assume that it will continue to be used. It is just that in this book it is applied to inductive arguments as well as deductive arguments.

Another issue is that this book has a section on relevance but is using the term differently to the way it is used in the Higher Course. In the course relevance is to do with evaluating an argument but in this book it is used for weeding out material prior to reconstructing an argument.

Finally, the book has a very precise definition of what is meant by an inductively forceful argument. It means an argument where the conditional probability of the conclusion relative to the premises is greater than one-half, but less than 1. It is important to note that this is different to ordinary usage where when we say a statement is probably true we usually mean the chances of it being true are substantially greater than a probability of 50% (This is why Bickenbach and Davies can speak about cogent but weak arguments.)

What is the Argument?

What is the Argument? by

Maralee Harrell

This book would make a valuable addition to any teachers' library. As always there is much in the book that isn't relevant to the Higher Course but its opening chapters on arguments and argument diagrams is the best I have seen. The style of argument diagram is slightly different to those that have appeared in SQA question papers but they are in all respects equivalent and pupils should benefit from seeing different kinds of presentation. What makes this book particularly valuable is that it then applies this method of presenting arguments to both Descartes and Hume and following through the diagrams should assist pupils in understanding these mandatory texts. There is also material on utilitarianism and Kant but not on the parts that are particularly relevant to the Higher course. One negative point is the way Harrell deals with the malicious demon. In a brief paragraph Harrell suggest that Descartes introduces the demon because it 'might be that Descartes hasn't thought of all the possible kinds of belief.' It is noteworthy that Harrell doesn't attempt to relate this to the text. This isn't surprising as there isn't anything in the text to warrant this claim. Descartes tells us why he is introducing the demon and he doesn't say anything about doing so to mop up any areas of belief that haven't yet been brought into doubt.

Some of Harrell's teaching notes on argument diagrams, which clearly formed the basis of one of the chapters to this book, are available here and various other places.

Schaum's Outline of Logic

Schaum's Outline of Logic,

by John Nolt, et al

This is particularly useful for its chapter on argument diagrams with clear explanations and lots of useful worked examples. It is worth noting that its method of bracketing and numbering the statements is not followed by writing a key with standalone statements. Students on the Higher course should be familiar with this additional step. Elsewhere, the book equates deductive arguments with valid arguments. This is not the definition used by the Higher course which allows the formal fallacies to be deductive arguments even though they are not valid. The book also uses a different method of argument evaluation.

Reviewed by CP, August 2018

Descartes

It is important to be careful when selecting books on Descartes. Books are written for a number of different purposes and not all are suitable for preparing candidates for this course. In particular, quite a number of books give an abbreviated account of Descartes’ method of doubt moving from deceit of the senses onto the dream argument and then straight onto the malicious demon making no mention of the deceiving god. Others make only a cursory mention of the deceiving god as if the text says,

‘...how do I know that God has not brought it about that I too go wrong every time I add two and three or count the sides of a square, or in some even simpler matter, if that is imaginable?

But perhaps God would not have allowed me to be deceived in this way, since he is said to be supremely good.

...I will suppose therefore that not God, who is supremely good and the source of truth, but rather some malicious demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me.’

However, this misses out a large portion of text (click to view) with which candidates should be familiar.

Some books also give an overly simplified account of the trademark argument.

This is not to suggest that these books are necessarily ‘wrong’. They are being selective and writing in a way that may well be appropriate for their target audience. That audience isn’t always going to be students on this course.

The Routledge Guidebook to Descartes' Meditations

The Routledge Guidebook to Descartes' Meditations, by

Gary Hatfield

This is one of the books recommended in the recent Course Specification and it is an excellent recommendation.

It may be that those teachers who studied philosophy some years ago will think they remember everything they have to know from their first year at university and now only need to explain the pupil notes. Perhaps so but possibly not. It used to be that philosophy departments drew a distinction between doing philosophy and studying the history of ideas. The classic texts were mined for arguments that could help students understand debates in epistemology and other areas. There is now a greater appreciation of the need to understand Descartes in the context of his own time and to understand his own purpose in writing. This part of the Higher Course is now text based and it important not to gloss over parts that might have been overlooked when using a different approach. Hatfield’s commentary is an excellent guide for any teacher who wants to get to grips with what Descartes was trying to do.

The Course Specification says, ‘The method of doubt: Descartes’ presentation of his philosophy through the voice of a first-person narrator, a meditator, who is re-evaluating his beliefs and starting again right from the foundations.’ Hatfield helpfully maintains the distinction between Descartes the author and the character of the meditator by referring to the meditator as ‘she’.

In the second set of replies Descartes writes, ‘This is why I wrote 'Meditations' rather than 'Disputations', as the philosophers have done, or 'Theorems and Problems', as the geometers would have done. In so doing I wanted to make it clear that I would have nothing to do with anyone who was not willing to join me in meditating and giving the subject attentive consideration.’ Hatfield explains how the structure of the Meditations echoes the religious meditations of Ignatius of Loyola, writings that Descartes would have undoubtedly known from his education in a Jesuit school.

Both the background information and the paragraph by paragraph explanation of the text will be an invaluable aid to the teacher who wants to be confident in their presentation of this part of the course.

Descartes: A Guide for the Perplexed

Descartes: A Guide for the Perplexed,

By Justin Skirry

This book contains material that goes beyond that expected of candidates but is very useful background reading for teachers who want to refresh their understanding of key parts of the Meditations. The author gives a clear account of the method of doubt showing how it exemplifies Descartes’ approach to reasoning and how he differs from the then current Aristotelian syllogistic approach. The material on the method of doubt and on the cogito is essentially descriptive and there is no discussion of standard criticisms. His account of the method of doubt includes the deceiving god and the often overlooked point that the non-existence of god would lead to the same doubt. However, there is no mention of the malicious demon. There is helpful material on whether the cogito is a deduction or an intuition. The material on Descartes’ metaphysics will be helpful to teachers who should ideally understand things in greater detail than might be expected of their students. The causal adequacy principle and the trademark argument are well explained but, again, the essence would have to be distilled down for Higher pupils.

Hume

Resources found helpful In preparing to study Hume’s Enquiry.

Utilitarianism

Resources found helpful in preparing for the study of utilitarianism.

Kant

Resources found helpful in preparing for the study of Kantian ethics.