Some issues with Q5

Update: The published marking instructions have now been amended so they no longer misidentify the statement about the social media campaign as a premise. It still seems that the only way to gain the third mark is to interpret the passage as having an intermediate conclusion when this isn’t a necessary reading. To be fair, changing this would have been more complicated. It would have required adding something rather than just deleting a line and adjusting the numbering. Although there is no mention of this question in the Course Report I am told they were aware this question 'didn't function well' and was part of the reason the grade boundaries were adjusted.

Higher Philosophy 2019, Paper 2, Question 5

There isn't anything obviously wrong with the question itself although it does suggest that everything in the paragraph is part of the argument and that is an issue:

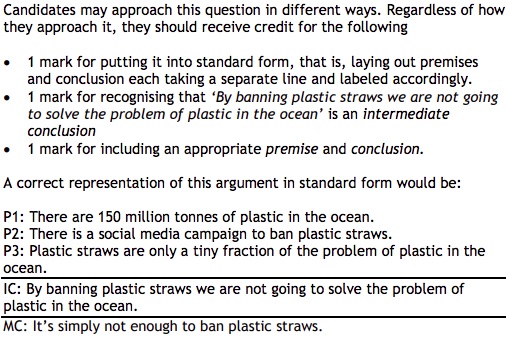

but there are definitely some issues with the SQA's marking instructions:

The most obvious problem is that the statement labelled P2 isn’t a premise.

This is easy to demonstrate. If you write the following you have an argument:

Plastic straws are only a tiny fraction of the problem of plastic in the ocean.

THEREFORE

By banning plastic straws we are not going to solve the problem of plastic in the ocean.

If you then add in P2

There is a social media campaign to ban plastic straws.

it makes not the slightest difference to whether you should accept the conclusion. You might also ask whether the following makes any sense: 'There is a social media campaign to ban plastic straws therefore by banning plastic straws we are not going to solve the problem of plastic in the ocean'. It obviously doesn't. Nor does it help to try and combine this statement with any of the other putative premises. This is because it isn't a premise, it's doing no work in the argument, it's simply the context for the argument. Someone notes there is a social media campaign to ban plastic straws and then says 'However, ... (and then comes the argument that what the social media campaign is working on isn't enough).

Once it is realised that P2 isn't a premise a question has to be asked about P1. If the same test as above is applied to P1 it can be seen that adding P1 also doesn't affect whether or not the conclusion should be accepted. If P3 had been worded differently and had said, 'Plastic straws contribute one million tonnes of plastic to the ocean', then you would need something like P1 to get to the conclusion but because P3 already tells you that plastic straws are only a tiny fraction of the problem P1 isn't needed. In these circumstances it has to be asked whether it is best to consider P1 as a premise or as part of the background description that is carried on by P2. One way of answering this is to look at the original passage and ask, 'What function does the word "However" play in this passage?' The natural way of reading this is to take 'However' as introducing a response to the description that has just been given. The word acts as an introduction to the little argument that follows. This gives us the following reading:

Here is a description of an environmental problem:

There are 150 million tonnes of plastic in the ocean.

And here is something that people are doing about that:

There is a social media campaign to ban plastic straws

However, (and here I'll tell you why this campaign won't solve the problem)..

Plastic straws are only a tiny fraction of the problem of plastic in the ocean.

THEREFORE

By banning plastic straws we are not going to solve the problem of plastic in the ocean.

Finally, there is the question of whether this passage does or does not contain an intermediate conclusion. The marking instructions are clear that it does. Not only is an intermediate conclusion given in the supposedly correct representation but the way the marks are allocated means it is only possible to gain the full three marks if the candidates' answer contains an intermediate conclusion. But surely the argument doesn't have to be read that way. It depends on whether the opening and closing sentences of the passage are taken to be saying the same thing or whether the opening sentence is saying something more. Part of the difficulty is there is no prior context. We don't know what prompted the comment. A particular tone of voice might well decide the matter but that isn't available.

The problem is the phrase 'It's not enough' is ambiguous. This is ironic given that recognising the impact of ambiguity on an argument is part of the course. This ambiguity is much more realistic than the contrived example in Question 6 but like most realistic examples may not be immediately obvious. 'It's not enough' can either have a purely quantitative interpretation, whereby someone points out that the amount of what is being considered hasn't reached a level where a particular consequence will follow, full stop, or it can have a moral dimension where it is claimed that a particular moral obligation hasn't yet been fulfilled with the implication that more needs to be done. These two meanings are illustrated in the following sentences:

'Yes, it's very windy but it's not enough to blow the fence down'

'If you see someone fall and hurt themselves it's not enough to hope they'll be OK'

The issue is whether it is the quantitative or moral usage in the opening sentence. Perhaps the word 'simply' nudges it in the direction of the moral interpretation but if that hasn't decided it for you then everything else in the paragraph is about quantity and the closing sentence gives you the quantitative interpretation. It might even be claimed that to get to the moral conclusion you would have to supply a moral premise such as 'we ought to be solving the problem'. At best either interpretation seems possible and it is unfair to deprive one interpretation of the possibility of gaining that third mark.

It also has to be noted that in the context of the exam the candidate has just completed Question 4 where they have had to analyse an argument that has a similar structure with the conclusion at the beginning and then repeated at the end so they will have come to this question already primed to see the structure that way. This makes it doubly unfair on the candidate.

Additional thought: Another way of reading the passage is to say the same argument is given twice. People often repeat themselves, they say one thing and then say the same thing but in a slightly different way. (Did you see what I did there?) Read this way the first two lines present a simple one premise argument, then you get the aside about the social media campaign, and then, in response to the aside, you get the same one premise argument repeated but put the other way around.