Exemplar essay answers

| Site: | Higher Philosophy |

| Course: | Higher Philosophy: Some notes and observations. |

| Book: | Exemplar essay answers |

| Printed by: | Gjestebruker |

| Date: | Friday, 4 April 2025, 7:25 PM |

1. The purpose of these exemplars

These exemplars were not written to illustrate a particular level of attainment. They haven't been given a mark. Nor were they written to give the definitive correct answer to the set question. They were written for pupils to illustrate how they might take the material from their notes and from class discussions and mould that material into an essay answer. They were intended to be used as part of feedback after the pupils had attempted to write the essay for themselves.

Teachers are best placed to know what material they have covered with their classes and what topics have come up in class discussions. Individual teachers, therefore, are in the best position to write such illustrative essays for their own classes and that might be more useful than simply issuing essays that were written for a different class who had different notes and different discussions.

2. Evaluate Descartes' method of doubt

In the past it might have been expected that a candidate would be able to say if Descartes was successful in overcoming his doubts in the rest of the Meditations but now, since Med VI is no longer part of the course, it is likely to be either a standalone question or somehow linked in with a question on the cogito.

In 2012 SQA asked a series of linked short answer questions:

At the beginning of Meditation 1 Descartes tells us what strategy he is going to use

(a) Describe the strategy that Descartes says he intends to use.

(b) Describe how Descartes implements this strategy in the rest of Meditation 1.

(c) Evaluate the arguments Descartes uses to arrive at the Cogito.

Evaluate Descartes' method of doubt

Exemplar answer.

| 1 | ‘Method of Doubt’ refers to the strategy Descartes uses in Meditation I and the first part of Meditation II to find something that is certain. In the synopsis prior to the Meditations proper Descartes says that this method is designed to free us from all our preconceived opinions, provide the easiest route by which the mind may be led away from the senses and to ensure that anything we subsequently discover to be true is free from doubt. At the beginning of Meditation I he says he will withhold his assent from any opinion that is not absolutely certain. He will not set about doubting each individual belief but instead attack the basic principles on which his former beliefs rested. Central to this is an attack on the reliability of the senses. |

| 2 | It is common to read that Descartes is using sceptical arguments to ultimately prove the sceptics wrong. It is true that he wants to find something certain but his main target is Aristotelian empiricism. Again in the synopsis he emphasizes the need to doubt especially material things. This emphasis is seen in Meditation I for although he uses the deceiving god argument to doubt mathematics and geometry the emphasis is on the possibility that the meditator is mistaken in his belief that there is any kind of external world—that there is no earth, no sky and no extended thing. When the malicious demon is introduced there is no mention of doubting mathematics or reason but there is again an emphasis on doubting all external things including his own body. |

| 3 | If the deceiving god argument and malicious demon hypothesis can bring doubt on all things then a question arises as to why Descartes needed to bother with drawing attention to sensory errors and the possibility that life is a dream. The answer is that Meditation I is not just an exercise in proving a point but rather is an attempt to change the way people think. In the Replies he says he wants people to spend ‘several months or at least weeks’ considering these issues before moving on. The difficulty in getting people to change their way of thinking is highlighted by the way he introduces the malicious demon. He has already established with the deceiving god argument that doubts can be raised about all his previous beliefs and emphasises that this is a carefully thought out conclusion. However, in the role of meditator, he says the old opinions keep coming back and that is why he introduces the possibility of a malicious demon intent on deceiving us. As a psychological tool the demon is going to be more effective than the deceiving god. |

| 4 | Ultimately, it doesn’t matter that the sensory deception and dreaming arguments are not watertight for they are just being used to soften up the meditator so that the universal doubt of the deceiving god and malicious demon are more effective. However, they do also prepare the way for the possibility that we make mistakes even if there is no all powerful being. |

| 5 | Few will question that we are sometimes mistaken in the way we see things and it doesn’t really matter that the senses are often the means of correcting these mistakes. The crucial point is that the senses don’t always correct themselves and it is necessary to use reason to work out that the sun is much larger than it appears or that the Earth rotates around the sun rather than vice versa. A key reason for Descartes’ attack on the reliability of the senses is that he wanted to give a firm foundation to the new science exemplified in the work of Galileo |

| 6 | From a sceptical point of view the dreaming argument is the weakest argument in Meditation I. It may well be that when we are asleep we cannot tell that we are asleep but it doesn’t follow that when we are awake we cannot tell that we are awake. Indeed, it is only possible to have this discussion about dreaming because we can tell the difference! The argument might be salvaged by saying that our supposedly awake experiences are in some ways similar to a dream like state in that we are not perceiving the world correctly and that our dreams are really more like dreams within dreams but this isn’t the argument Descartes puts forward. In a sense, though, this misses the point. For Descartes the crucial thing is that even if the dreaming argument did work the dreams have to be of something and the truths of mathematics and geometry would still hold. The purpose of the dreaming argument is to highlight what it would fail to bring in to doubt and so prepare the way for the deceiving god argument. |

| 7 | By the start of Meditation II the meditator can say that even if there is a malicious demon absolutely intent on deceiving him in all possible ways that demon cannot make him doubt his own existence. It has been questioned whether Descartes has actually doubted everything—e.g. he knows what thinking is and what doubt is—but Descartes dismisses this saying that he only intended to rid the mind of ‘preconceived opinions’ i.e. those based on previous judgments. He accepts that it is impossible to rid the mind of all notions. After all, there has to be some cognitive content to engage in the activity of doubting. Descartes' purpose was to find certain knowledge of something existing and with the method of doubt ending in the cogito he seems to have achieved that. Even if there are aspects of the cogito that can be questioned — is he entitled to use the word ‘I’? — and even if it is not clear that he can build anything on this foundation, the cogito is more immune to doubt than the evidence of the senses and so, from that point of view, his method of doubt can be judged a success. |

991 words

Notes

- In any essay it might be worthwhile to begin by defining any technical terms or phrases that are used in the question. In this first paragraph I am just clarifying what it is that is meant by 'method of doubt'.

- This paragraph clarifies the purpose of the method of doubt and argues that it is primarily aimed at the Aristotelian empiricists rather than the sceptics. It is worth noting that many texts will not mention the empiricists and will focus entirely on the idea that Descartes is trying to prove the sceptics wrong. For that reason it is important to present the case and not just assume the marker will immediately understand this interpretation.

- Notice that I am not just plodding my way through the method of doubt step by step. Instead, I am drawing back and commenting on the structure of the Meditation One. This enables me to both make an analytical point and at the same time let the marker know that I am fully aware of the various stages the reader is being taken through.

- This is a linking paragraph containing some brief evaluative observations that will be expanded on in the following paragraphs. It serves to put those later paragraphs into context. It also shows detailed knowledge of the text by mentioning the point that the doubt still exists even if there is no god.

- Some essays might spend a whole paragraph explaining how the senses sometimes deceive us and another whole paragraph criticising this by saying that the senses can correct our mistakes. I have captured all of this in one sentence and then gone on to give an evaluation of this criticism. I have also managed to link this evaluation back to Descartes' overall purpose.

- Again I begin by demonstrating to the marker that I am familiar with the standard problems with the dreaming argument and then spend time evaluating those standard criticisms.

- This is a fairly densely packed paragraph. I am letting the marker know that I understand the various criticisms mentioned but also manage to wrap up the essay by coming to a conclusion — that the cogito is more immune to doubt than the evidence of the senses — a conclusion that follows on appropriately from the way I set up the essay as an account of the method of doubt as a challenge to the Aristotelian empiricists.

3. Hume on Causation 1

In this response I am trying to illustrate how it is possible to answer an 'analyse and evaluate' type of question without getting 'bogged down' in lots of description.

Analyse and evaluate Hume's theory of causation.

Exemplar answer.

| 1 |

Hume claims that that knowledge about causes is never acquired through a priori reasoning, i.e reasoning prior to experience, but always comes from our experience of finding particular objects are constantly associated with one other. To illustrate and support this claim he says that Adam could not have inferred from the fluidity and transparency of water that it could drown him, or from the light and warmth of fire that it could burn him. Hume provides two arguments. Firstly, he says that the cause and the effect are separate things and no matter how hard we look we can never discover the effect in the cause. A modern illustration might be the switch coming down and the light coming on are separate events and, prior to experience, there is nothing in the first that suggests the second. Secondly, he says that even when the casual relationship has been suggested we cannot observe the necessity of that effect following that cause. Without contradiction we can imagine all sorts of other things happening. At the end of section IV part 1 Hume rejects the objection that applied mathematics, what we might call science, is an exception to this claim because science itself is just the result of accumulated observations. |

|

Hume’s position is open to a number of objections. |

|

| 2 | Firstly, Hume says that we need to observe constant conjunctions and says we become sure of the result only because we have experienced many events of that kind. This is not always the case. It does not seem necessary for the child to burn itself on the hot iron more than once to determine what caused the pain. Hume might respond that once we have the notion of cause and effect in one situation we can then apply that as a hypothesis in novel situations. This may be so but it does, somewhat, undermine his point about constant conjunctions. A more nuanced position might be that the more times something happens the more convinced we can be about the causal relationship although it would be important for Hume to say that this isn’t a reasoned position but simply one of custom and habit. |

| A second problem is that the conjunctions are not always constant. Putting the light switch down doesn’t always result in the light coming on. Sometimes the bulb explodes, sometime a fuse blows and there is nothing obvious to see. The fact that we are puzzled and frustrated when this happens shows that the lack of constancy does not undermine our belief in the causal connection—we still assume that the switch should have caused the light to come on. Presumably this is still the case for little children who have not yet learned anything about the underlying science. Again a more nuanced position might be more appropriate—the stronger the correlation the greater the confidence in the cause and effect relationship. | |

| Unfortunately, a third problem is that even with constant correlations we, and even young children, don’t form a cause and effect assumption. With traffic lights the single green light is always followed by the single amber light but it seems unlikely that anyone ever infers that one is causing the other. To this Hume would undoubtedly point out that he said the causal chain doesn’t have to be direct and gives the example of seeing light and inferring heat not because the light causes the heat but because both are caused by the fire. However, this move on Hume’s part only seems convincing because we already know something about fire, heat and light. The young child might know nothing about electric circuits so, if Hume is correct, presumably should conclude the green light causes the appearance of the amber light. | |

| A fourth problem is that Hume’s claim that specific causal relationships can only be identified following experience does not seem to be true. There are examples from science where accurate causal predictions were made prior to experience and then subsequently proved experimentally. Einstein predicting the way in which gravity bends light being one such example. Hume might say this would be the kind of example he meant when saying that applied mathematics is based on prior observation. However, the Einstein example seems to go way beyond the kinds of things Hume had in mind when he made his claim. | |

| Lastly, Kant pointed out that experience is not a simple matter. To use a more modern way of putting it we have a stream of data coming our way and we have to process that in some way in order to make sense of it. We use certain categories to make sense of the world and one of those categories is cause and effect. If the category of cause and effect is one of the ways in which we make sense of experience then it cannot be experience that tells us about cause and effect. | |

| In conclusion, I would say that Hume’s examples look convincing because he has chosen examples that fit with his theory. However, there are too many examples that don’t fit with his theory and it seems likely, and perhaps not surprising given when he was writing, that Hume is using an overly simplistic view of human psychology and our understanding of cause and effect is much more complex than simply observing constant correlations. |

886 words

Notes

- In an essay like this it will always be a judgement call as to how much background material needs to be included. What I have tried to do in this opening paragraph is to give the bare-bones of Hume's position and flag up those aspects that are important for the evaluative points dealt with later in the essay.

- In this and the following paragraphs, rather than just give a criticism, as if that was enough to demolish Hume's position, I have tried to discuss the criticism and to consider whether a response to the criticism would be adequate.

4. Hume on Causation 2

This response plays around with a conundrum facing teachers when preparing pupils on this part of the course—how do you evaluate Hume's view of causation when a key aspect of Hume's view is not part of the text pupils are required to study?

To what extent is Hume’s view of causation convincing?

SQA Specimen Question Paper 2016

Exemplar answer.

| 1 | There is something very puzzling about what Hume says concerning cause and effect. In Section II Hume had argued that all ideas are based on impressions, however, in Section IV Hume claims that although our idea of cause and effect is based entirely on experience that experience is simply the experience of two events being constantly conjoined—we don’t have an impression of what makes the cause the cause and what makes the effect the effect, and we certainly don’t have an impression of the necessity that ties them together into a cause and effect relationship. Given what Hume has said in sections II and IV it is not clear how we can have any idea of cause and effect. |

| 2 | The purpose of Section IV Part One is to establish the claim ‘that knowledge about causes is never acquired through a priori reasoning, and always comes from our experience of finding that particular objects are constantly associated with one other’. Hume claims that Adam even if he were capable of perfect reasoning would not have been able to tell, prior to experience, that water would drown him or that fire could burn him. He claims that the qualities of an object that appear to the senses never reveal the causes that produced the object or the effects that it will have. If a stone is held in the air and released then, prior to experience, there is nothing in the stone that gives the idea of a downward rather than upward motion. Furthermore, prior to experience, there is nothing we can say about the necessary connection between the cause and the effect—I may think I know what will happen to the second ball when struck by the first but, prior to experience, I might be able to think of a hundred different events that will follow from the first and have no way of choosing one over another. |

| 3 | Even if there are exceptions it seems plausible that in the normal course of events Hume is right that knowledge of particular causes and particular effects depends on experience. However, this doesn’t answer our original problem—knowing what effect follows what cause is one thing but having a general idea of cause and effect is something else and cause and effect is more than just correlation or constant conjunction it contains the notion that the effect is dependent on the cause and that the cause will necessarily have that effect. |

| 4 | In Section VII Hume considers and rejects various possible sources for our idea of a necessary connection. One of these is our ability to will certain events such as the movement of a limb. Hume may be right that we don’t understand how that desire results in the desired effect and it may be only through experience that we discover what we can and cannot will and we may still only have an constant conjunction between my willing something and it happening, however, contrary to his previous examples there does seem to be something present in the first event (e.g. my willing my arm to raise) that would suggest the effect (my arm raising). |

| In Part Two of Section VII Hume manages to avoid the conclusion that the necessary connection between cause and effect is a meaningless concept by saying it emerges from the way we feel after seeing several occurrences of the supposed cause and effect. He says, “the feeling or impression from which we derive our idea of power or necessary connection is a feeling of connection in the mind—a feeling that accompanies the imagination’s habitual move from observing one event to expecting another of the kind that usually follows it.” This solution is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, the relationship between an idea of necessary connection and the inner experience of expectation doesn’t seem to be just a faint copy as in his earlier examples of inward impressions. Secondly, causes and effects do not always depend on any expectation for both are simultaneously present—I may see the pedals and the back wheel both turning; I may see the foam cushion compressed and the person sitting on it. | |

| The constant correlations of the bicycle and the cushion present another problem—since they occur simultaneously, if that is all there is to it, then it should be reasonable to come to the conclusion that the back wheel is causing the pedals to turn and so operating the person’s feet, as might happen in a mechanical model where a hidden motor is driving the back wheel, or that the cushion is somehow sucking the person into the seat. That the explanation invariably goes in the other direction is likely due to the importance we place on agency and this would suggest that agency is more involved in our understanding of cause and effect than Hume would allow. This is further supported by the way humans constantly attribute agency even when it doesn’t exist as when we say the flower wants to turn towards the light or the water wants to flow down hill. Whether this emphasis on agency derives from our own experience of being agents or whether it is something we bring to the world still needs to be resolved. | |

| 5 | In Section II Hume said that anyone who wanted to refute the claim that all ideas were based on impressions only had to provide an example of an idea that couldn’t be traced back to a relevant impression. Hume’s account of the origin of the idea of cause and effect seems forced and it might only be an empiricist dogma against innate ideas that stops this being just such a counterexample. Given the problems with Hume’s account and our greater understanding of developmental psychology it seems better to side with Kant who claimed that we cannot get the idea of cause and effect from experience because cause and effect is one of the concepts we use to make sense of experience. |

988 words

Notes

- Many essays with this title will be a run-through of the various criticisms that can be made of Hume’s analysis of causation. This essay takes a different approach and considers just one major issue and it is this issue that is flagged up in the introductory paragraph. It would be tempting at this point to summarize what Hume says about impressions and ideas but some things have to be missed out and given the title and the limited time it is better to focus on Section IV Part One.

- This paragraph summarizes Hume’s arguments. Although their purpose is to show that our understanding of cause and effect does not rely on reason in doing so they also make clear that there is no direct impression of the cause and effect relationship.

- This paragraph clarifies our problem. Knowing the source of our idea of cause and effect is a different question from how we discover particular cause and effect relationships. There is no time to develop ‘even if there are exceptions’ but it is alluding to things like Galileo and Einstein’s thought experiments.

- These two paragraphs draw on parts of the text that are not specified as part of the course. This means that SQA cannot require/expect this knowledge or set questions on it. However, this doesn’t mean you cannot bring it into the discussion. This is somewhat similar to the fact that SQA doesn’t specify any particular criticisms. Anything you say that is relevant and helps you build a case will be given credit.

- Most essays will probably focus on either Section II or on Section IV. This essay shows how material can be drawn from more than one place to make an argument. In this final paragraph it is important to arrive at a final conclusion that follows on naturally from what has been said in the rest of the essay.

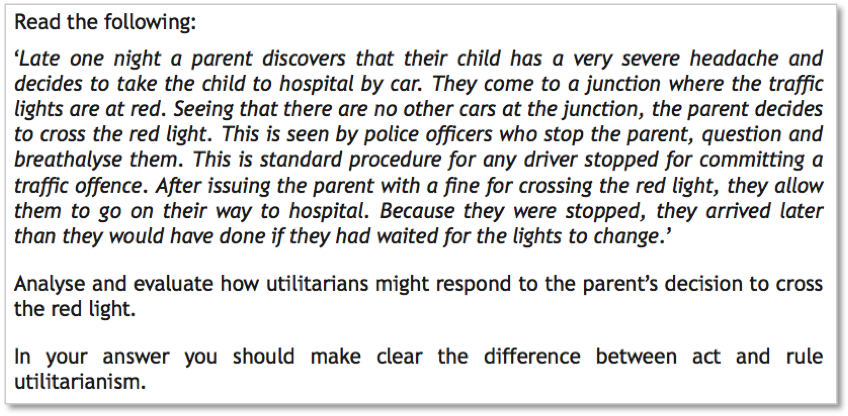

5. Utilitarianism 2018

.

.

SQA Higher Philosophy 2018

Exemplar answer.

| 1 |

This scenario highlights a number of important aspects of utilitarianism in particular the role of consequences and the use of rules. We are not told if the driver was using utilitarian principles in order to decide what to do or whether they were just trying to get to hospital as quickly as they could but I shall assume it was the former. |

| 2 | Utilitarianism is a consequentialist theory, i.e. it is the consequences that determine whether something is right or wrong. If the consequences are such that no other outcome can produce a greater balance of happiness or pleasure then that is the right thing to do. The problem is that consequences, by their very nature, are uncertain. Things may not turn out the way you expect. We see this clearly in the scenario. One way utilitarians might deal with this is to draw a distinction between actual consequences and intended consequences. The actual consequences can determine whether the action is the right one but the intended consequences can be used to judge the morality of the decision. Mill made this point in a footnote in Utilitarianism, albeit a footnote that didn’t appear in later editions. On this basis, ignoring other factors, the parent’s decision might be judged moral even though it turned out to be the wrong thing to do. |

| 3 |

However, there is a further problem in that when consequences are ultimately unknowable, even when the outcome of a particular choice is finally known, to know whether it was the action that maximised happiness it needs to be compared with all the other possible outcomes that can never be known. Some people regard this as a fatal flaw in any consequentialist theory but utilitarians might say that at any stage of the calculations it is only necessary to consider the reasonably foreseeable consequences. In the scenario it would then be unnecessary, for example, for the parents to consider the likelihood of being seen by a better doctor if they arrived later having waited at the lights. |

| 4 5 |

An additional complication, which may change the evaluation of the parent’s decision, is the place of rules in utilitarian thought. Given that Bentham argued against a starving beggar stealing bread from a rich person’s house on the grounds that it would not maximise happiness because it would undermine law and order, one can assume he would argue that in the scenario the parents should not break the rules of the road for the same reason. Obeying the law and following the rules can also be justified by saying that in practice it is more likely to result in people making the right decision than if they try to do the calculation quickly especially when personally involved and subject to bias. In the scenario it can be questioned how objective the parents can be when their child is in pain. However, the claim that breaking the law will always undermine the law ultimately leading to less happiness is unconvincing; it doesn’t seem correct to say that individual decisions in extreme situations will change general behaviour. Nevertheless, society does need rules and not enforcing them will lead to them falling into disrepute. In the scenario, then, it is plausible to say that the utilitarian driver might have been right to calculate that breaking the law in this instance would minimise pain but the police and the legislators would be right to calculate that the law should be enforced. Tensions such as these might suggest that rule utilitarianism is a better option. Act utilitarianism says that an action is right if it maximises happiness; rule utilitarianism says that an action is right if it conforms to a rule which is in place because having the rule maximises happiness even if it means that on this particular occasion the resulting action doesn’t maximise happiness. It is likely that a rule utilitarian will have a rule that says, ‘Obey the law’ in which case the parents should not have jumped the lights. However, they may recognise that in exceptional circumstances it is legitimate to break the law so the rule might be, ‘Obey the law unless, in exceptional circumstances it is clear that it is better to break the law’. It then becomes a debate as to whether this is one of those exceptional circumstances. Rule-based systems also run into the problem of conflicting rules and so rule utilitarians may have a tie-breaker which says, ‘If there is a conflict between two rules then act optimifically’. It would seem that in practice, then, rule utilitarianism collapses into act utilitarianism. |

| 6 |

In summary, although they define the right action in different ways and although they may get there in slightly different ways, both act and rule utilitarians would advise the parents that they should obey the law unless it is very clear indeed that this is an exceptional circumstance. If it genuinely was an exceptional circumstance then, hopefully, the police will have escorted them to the hospital rather than having given them a fine. |

| 7 |

A simplistic understanding of utilitarianism would suggest the parent breaks the law and, while in some circumstances this may have some immediate appeal, a more considered appraisal of the situation suggests the parent should normally obey the law. Although there are undoubted problems with predicting the future, as an essentially pragmatic theory, utilitarianism has an adequate response to this challenge and gives good guidance as to why the law should be obeyed. |

905 words

Notes

- The purpose of a scenario is to force you to select the relevant information from everything you know about the theory. Before starting the essay it is important to know what aspects of the theory you are going to write about and which ones you are going to ignore. It is not a bad idea to use the introduction to flag up what it is that you have selected. I have used the second paragraph to clarify how I was going to interpret an aspect of the scenario that wasn't clear. It is often the case that scenarios are lacking in detail and it doesn't do any harm to specify your assumptions—but be careful, don't turn the question into something that it isn't.

- There isn't only one way of writing an essay but in this paragraph I have defined a key concept, identified a problem with that concept, responded to the problem and linked it all to the scenario.

- Having already defined consequentialim I now present an additional problem that is a development of the previous problem and then I offer a suggestion as to how utilitarians might respond to that objection. To gain the higher marks in an essay you should go beyond description plus criticism and aim for description plus criticism plus response.

- Given the instruction in the essay question it would have been entirely in order to begin the essay with appropriate definitions of act and rule utilitarianism and work forwards from there. I have chosen to start with consequences and their problems because it then enables me to present the act and rule utilitarian use of rules as a response to some of the problems of calculating the consequences. In another essay this might have been greatly expanded.

- Somewhere in this essay it is essential the definitions of act and rule utilitarianism are clearly stated. A simplistic understanding of utilitarianism will say something like 'act utilitarians concentrate on the act whereas rule utilitarians use rules'. This is at best half true. In defining what is right act utilitarians will concentrate on the action and rule utilitarians will concentrate on the rules but in making a decision about what to do act utilitarians will happily use rules. In any essay on act and rule utilitarianism this should be made clear.

- This summary takes the previous points and quickly applies them to the scenario.

- The conclusion should follow from everything that has been said before and, whilst the various critical comments offered throughout the essay will count as evaluation, it isn't a bad idea to make some kind of final assessment as to the adequacy utilitarianism as a guide as to how to judge the parent's action.

6. Kantian ethics 2015

“Kantian ethics is not a useful ethical theory.” Discuss.

SQA Higher Philosophy 2015

There are different ways of answering this question. You might give a quick overview of Kantian ethics to set the scene and then discuss the strengths and then the weaknesses (or vice versa) before summing up with a conclusion. However, this might lead to a somewhat fragmented essay that doesn’t ‘flow’. I have chosen to describe Kantian ethics and to use each piece of description as a peg on which to make some observation about a strength of the theory. I follow that by outlining some important criticisms. To help give the essay some structure the criticisms generally follow an order determined by the opening paragraphs but this isn’t adhered to rigidly. It would be possible to peg the weaknesses to the description and then follow with the strengths but since I knew that I was going to conclude by suggesting that, overall, Kantian ethics is not a useful theory it was better to have the criticisms leading into that conclusion. The conclusion doesn’t add anything new but does build on what has already been said earlier in the essay.

Exemplar answer.

| 1 |

Kantian ethics is deontological, i.e. it is based on duty. This is not a duty to others or to particular authorities it is the duty to follow the moral law within. This inner moral law is based on reason. The right thing to do is determined using reason and logic without making any reference to possible consequences. This idea of a moral duty fits with our intuition that morality is about obligations. From a human point of view if people are encouraged to focus on consequences they are likely to be influenced by whether or not they prefer a particular outcome. Consequences are also impossible to predict with certainty. Kantian ethics avoids both these problems. Its emphasis on reason also chimes with our idea that it is wrong to be guided by emotions. When we make a moral choice we should make it for the right reason. |

|

The categorical imperative, the inner moral law, comes in a number of formulations but of the two most commonly cited the first is, ‘Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law of nature’. A maxim is your own personal rule, which may be a good rule or a bad rule. You can tell it is a good rule if it is possible to universalize the rule, i.e. if you can logically will it to be a rule for everyone. This is irrespective or whether, in practice, you can actually get everyone to follow the rule. This formulation captures another important feature of morality—moral rules should apply to everyone. I may make personal choices such as to take more exercise but if something is a moral rule then it isn’t just a personal choice, it is something that everyone should do in those circumstances. |

|

| 2 | There is some flexibility built into the system for if trying to universalize the rule leads to a contradiction in conception, i.e. you cannot even imagine such a world for the attempt to universalize the maxim removes the conditions that are needed for the maxim to make sense, then you have a perfect duty not to perform the action. For Kant lying and making false promises would fall into this category. On the other hand, if universalizing the maxim led to a contradiction in the will you have an imperfect duty to do what you were trying to avoid. Kant’s example would be giving to charity—not giving to charity means willing others not to help you when you are in need, something you cannot rationally will, so you should help others to some extent some of the time. |

|

The second formulation is, “So act as to treat humanity, both in your own person and in the person of every other, always at the same time as an end, never simply as a means.” This certainly captures the idea that morality is about treating people with respect and not just using others. |

|

|

Whilst it is easy to identify some significant strengths to Kantian ethics there are also some very significant weaknesses. It may be true that we cannot predict consequences with complete accuracy but in many areas of life where planning is required it is necessary to make reasonable predictions. Such planning is not irrational and so it is not obvious that a rational moral theory has to exclude a consideration of possible consequences. |

|

|

If consequentialist theories have the problem that people might be skewed in the prediction of consequences due to wishful thinking Kantian ethics is little better for by carefully selecting the maxim it is possible to find a permissible course of action. If you wanted to drive faster than the speed limit then the maxim ‘break the law’ would lead to a contradiction in conception for if everyone did it the meaning of ‘law’ would disappear. However, ‘drive as fast as it is safe to do so’ leads to no such contradiction. |

|

| 3 |

The first formulation also leads to counter-intuitive conclusions. Not only does it rule out lying to the pursuing murderer but it also requires you to avoid doing things that seem perfectly innocuous. Using your pvr to skip the adverts leads to a contradiction in conception for if everyone did it there would be no point in adverts as a way of funding programmes but it is difficult to see this as immoral. Rather, if everyone did it then the broadcasters would just have to find another way of funding their programming. |

|

The emphasis on reason and ‘treating humanity’ seems to exclude animals from any kind of ethical consideration and this seems wrong. Morality is not just about how we treat humans. |

|

| 4 | Even taken on its own terms the categorical imperative leads to the wrong conclusion. ‘Punch someone in the face if you don’t like them’ would lead to a contradiction in willing. According to the system this means you have an imperfect duty. It cannot be right to say that when you don’t like someone you should avoid punching them in the face some of the time and to some extent! |

| 5 | The appeal of Kantian ethics depends on selecting particular examples that lead to the right answer. Every moral theory will look good when this is done. It is commendable to seek consistency but consistency does not mean never breaking a rule. It just means if it is OK for me to break the rule then it is OK for someone else to do so in the same circumstances. Kantian ethics does not have a monopoly on using reason. While it may remind us of some important aspects of morality consequentialist theories which combine the use of reason with experience are more likely to offer a better practical guide. |

957 words

When you have limited time it is difficult to know what to include and what to leave out. I said very little about the second formulation but just enough in the first half for me to be able to include the criticism about it excluding appropriate consideration of non-human animals. There are plenty of other criticisms that I might have selected for example, torturing people to extract information in terrorist situations might plausibly pass the first formulation but fail the second. This would be a problem for Kant. When he gives his four examples (suicide, false promises, fostering your talents and helping the needy) it is clear that he expects both formulations to lead to the same answer. You don’t have to say everything you know—select the best bits for the essay you want to write.

- It is a good idea to start with the more general and basic concepts before getting into the detail.

- This paragraph is mainly description but I have made it evaluative by introducing it as an indication of flexibility. It is a necessary piece of description because I later want to include the criticism related to contradiction in willing. (See 4)

- Notice I just refer to the pursuing murderer. The examiner will know what this means and there is no time in this essay to tell the story. A weaker essay will use up a lot of the time/words on this. However, just mentioning it like this flags up that I know about the story. I get all the same credit but for very few words.

- See note 2

- It is important to answer the question. In this case the ‘question’ was an instruction to ‘discuss’ the quotation. Simply listing the strengths and weakness without coming to a conclusion would not be enough in an essay like this.

7. Kantian Ethics 2022

Some people think the law should be changed to allow assisted dying in cases where someone has a terminal illness and is facing the prospect of a painful and unpleasant death.

Explain and evaluate whether a follower of Kantian ethics would support such a change.

SQA Higher Philosophy 2022

It is important to remember that a scenario question is always just a device to get you to discuss the ethical theory. In this case, if you describe Kantian ethics, come up with a maxim that seems to allow assisted dying, and conclude by saying the theory gives clear advice and so is a helpful theory, it may appear that you have answered the question but you will have done so without engaging in any discussion of the theory. Unless there are clear instructions to the contrary, you should assume that an essay requires you to engage in some kind of debate. Before starting your essay it is always a good idea to ask yourself, 'What particular problems with the theory are highlighted by this scenario?' Your answer to this question will give you a very good idea of what you need to be writing about.

Exemplar answer.

| 1 |

The most natural reading of Kant is that he would generally disagree with voluntary euthanasia or assisted dying. |

| 2 |

Kantian ethics is a non-consequentialist theory, i.e. the consequences of an action are not what determine whether something is right or wrong. If something is right or wrong it is right or wrong irrespective of the consequences. In this particular case, whether or not legalising assisted dying reduces suffering or has unintended consequences for society is, for a Kantian, irrelevant. |

| 3 |

Kantian ethics is a deontological theory, which is to say we have a duty to follow the moral law and the moral law is summed up by the categorical imperative. There are two formulations of the categorical imperative that concern us: 1: Act as though the maxim of your action were to become, through your will, a universal law of nature. 2: Act in such a way as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of anyone else, always as an end and never merely as a means. Despite appearing quite different, as far as Kant is concerned these two formulations amount to the same thing. They should both lead to the same moral advice. If they don't then that would show there was something wrong with Kant's theory. |

| 4 |

Kant also distinguishes between perfect duties to self and to others, and imperfect duties to self and to others. Perfect duties allow no exceptions; imperfect duties are such that they must be carried out to some extent and some of the time. |

| 5 |

To illustrate the two formulations and and the various duties Kant uses four examples. His first example, which he applies to both formulations, is that we have a perfect duty to avoid suicide. Being a perfect duty there are no exceptions to this. His reasoning is as follows: With regard to the first formulation Kant says someone would be acting on the maxim 'For love of myself, I make it my principle to cut my life short when prolonging it threatens to bring more troubles than satisfactions.' The attempt to universalise this maxim, he says, leads to a contradiction in conception for then the principle of self-love would lead simultaneously to a desire to both prolong and shorten life. When there is a contradiction in conception there is a perfect duty not to act on the maxim. With regard to the second formulation Kant says if someone escapes their burdensome situation by destroying themself, they are using a person (in this case themself) merely as a means to keeping themself in a tolerable condition up to the end of their life. There is a perfect duty to avoid using someone (including yourself) as a means only so there is a perfect duty not to commit suicide. It is clear that the same reasoning would lead to the conclusion that it is always wrong to assist someone to end their life. |

| 6 | It is tempting to suggest there are alternative maxims that would lead to a different outcome. Certainly, the possibility of alternative maxims and the difficulty of identifying the correct maxim are criticisms of Kantian ethics but we should remember that this is Kant's own example and can, therefore, be taken as definitive as to how the theory should be applied. In any case, noting alternative maxims with a different outcome doesn't help us determine what a Kantian should do, it is, rather, a reason for saying the theory is flawed. If we look for another maxim because we don't like the outcome then we are acting like a consequentialist and trying to get a non-consequentialist theory to fit in with our consequentialist thinking. |

| 7 | The lengths to which Kant would go to ignore consequences becomes clear in his story of the pursuing murderer. You should not tell a lie even if you think it is the only way to save a life. These kinds of conclusions strike many people as absurd and are reason enough for rejecting Kantian ethics. However, we need to be careful. Rejecting the theory because we don't like the outcome looks dangerously like a fallacious appeal to consequences. Evaluating a moral theory by what it says about a single issue is, in any case, somewhat problematic. If, instead, it delivered a conclusion that was approved of that wouldn't necessarily make it a good theory as there might be all sorts of other reasons for rejecting the theory and if the theory is rejected because of these then what it does or does not say about assisted suicide becomes moot. |

| 8 | Kant rejects consideration of the consequences because they cannot be known for certain. It is true that consequences cannot be known with certainty but making reasonable predictions is an essential part of many life decisions, business planning, etc. If making reasonable predictions is such an essential feature of human existence it is, at the very least, odd that it should be excluded from moral reasoning. Kant wanted a moral law within that was a certain as the scientific laws that describe the natural world but perhaps there is no such law. Perhaps moral reasoning is always going to be more like a negotiation between competing interests. Kantian ethics reminds us to ask if it makes sense to want everyone to act in a certain way and to not make ourself an exception. It also reminds us to show respect to others and to treat people with dignity. However, it is probably wrong to assume that these considerations are by themselves enough to guide us when it comes to complex moral issues such as assisted dying. |

933 words

- This is a clear statement of the position I am taking but leaves open the possibility that there may be some situations where Kantian ethics might still allow assisted dying. For example, if 'humanity' is equated with our capacity for reason then perhaps it may be permitted for those in a permanent coma or even in cases of severe dementia. This would also open the possibility of involuntary euthanasia in these cases as well as voluntary euthanasia in accordance with an advance directive. It isn't necessary to discuss these cases in connection with the given scenario.

- Apart from those approaching the topic from a religious perspective, debates about assisted dying, whether for or against, are almost always a debate about consequences. It is crucial, therefore, to appreciate the non-cosequentialist nature of Kantian ethics. It is such a distinctive feature of the theory that it is likely to be a good starting point for many scenario based questions. An exception might be if the scenario is clearly directing you down the path of considering a conflict of duties.

- This is purely descriptive material. It is essential that you are able to state the two formulations. You also need to be able to explain and apply them. This is the essence of Kantian ethics. However, being able to accurately state them is a pre-requisite. A common error is to think that the second formulation is only about how you treat others. Note that it is about how you treat humanity 'whether in your own person or in that of anyone else'. The formulation rules out treating yourself as a means only. This is crucial to understanding why Kant is opposed to suicide.

- Making the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties helps to explain Kant's 'hard line' attitude to lying and, in this case, suicide.

- Knowledge of Kants four examples are not a required part of the course. They are not listed as part of the mandatory content. They are, however, included in Appendix 5 where it is said the relevant text extracts are included for 'illustrative purposes to exemplify the philosophical positions and arguments that candidates are required to study.' Even though they are not required, knowing Kant's own examples and how he used them will give a clearer understanding of how the two formulations work and what is meant by perfect and imperfect duties. In this essay it is obviously very helpful to know what Kant said about suicide.

- In this paragraph I am flagging up that I am aware of certain criticisms of Kantian ethics. In another essay this might have been developed by giving examples of maxims that would seem to lead to different answers.

- It is important not to get sidetracked into a long description of the pursuing murderer story. There is just enough here to show that I am familiar with it and it is a useful way of reinforcing the non-consequentialist nature of Kantian ethics and leads into the discussion of whether it makes sense to ignore consequences.

- In this final paragraph I have tried to give a balanced conclusion. By returning to the key issue of consequences flagged up at the beginning of the essay I hope to have given the essay a clear focus. A weak answer would simply say they disagree with Kant ignoring consequences. This paragraph goes further and argues why it is reasonable to take consequences into account. Nevertheless, I have also tried to draw out something useful from the Kantian approach whilst at the same time making it clear that I don't find it an adequate way of dealing with moral issues.