Key terms and concepts

| Site: | Higher Philosophy |

| Course: | Higher Philosophy: Some notes and observations. |

| Book: | Key terms and concepts |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 19 April 2025, 2:14 PM |

Description

Observations on the way terms are being used in this course and on how to avoid common errors.

Arguments in Action

There is a sense in which one can conduct an archeological dig on the Arguments in Action component and find traces of earlier courses and intended courses that never materialised. When the CfE courses were being developed in 2010 and 2011 there was an emphasis on skills. The traditional K/U, A & E had been known to be problematic in philosophy for all sorts of reasons not least because what passed as the skills of analysis and evaluation was, more often than not, simply the recall of somebody else's analysis and evaluation. One suggestion (one that wasn't taken up) was that instead of pushing on with these supposed skills thought should be given to the skills that philosophers actually use. There might have been three units — metaphysics, epistemology and moral philosophy — and they would be taught not just for their content but to highlight philosophical skills.

- Thought experiments were introduced because of Locke's locked room, the malicious demon, Nozick's experience machine and comparing hypothetical universes to arrive at Ideal Utilitarianism. Teaching thought experiments as a standalone topic became problematic and has now been dropped.

- Counter-examples were introduced because of Gettier examples, Hume's missing shade of blue and utilitarian examples of where the seemingly right thing to do fails to maximise utility.

- Analogical arguments were identified in Hobbes' water analogy, Paley on design, and Hume on the reason of animals. In this case the identified analogies have disappeared from the course but the topic of analogical arguments remains.

- Various fallacies were identified. Ambiguity in the form of equivocation was noted as a possible fallacy in Mill's defence of utilitarianism. Other fallacies were linked to other parts of the course, e.g. circularity in Descartes and Hume's avoidance of circularity in Section IV of the Enquiries, even though these fallacies never made it into the course.

- There were other issues of argument and criticism that were identified but were never singled out, e.g. self-contradiction was identified in the way in which hard determinist arguments might make themselves unreliable, Descartes claiming that you cannot doubt your own existence and Kant's contradiction in conception.

- Places in the units that utilised inductive and deductive reasoning were identified.

This integrated approach never materialised and there is now no expectation that links will be made between the Arguments in Action component and the other areas of the course. However, stepping back and recognising the skills and argumentative techniques that philosophers actually use may still enable some candidates gain a greater depth of understanding.

The Arguments in Action component now stands on its own and its various disparate topics have been effectively drawn together under the idea of informal logic. Although the emphasis now is on ordinary everyday argumentation it should not be forgotten that when philosophers write and argue they are rarely using some specialised language. They are usually using the same argumentative techniques as everyone else.

When considering the current content it is important to note that resources can differ even in their definitions of such well-established terms as ‘deductive’, ‘inductive’, ‘valid’, ‘sound’, etc. These pages highlight some of those issues but for definitive guidance on what is required reference should always be made to the SQA's own documentation.

Informal logic

When the first Higher Philosophy Course was launched twenty years ago it contained a choice between doing logic or moral philosophy. The contents of that logic unit will have been familiar to anyone who had taken a first year logic course at university. When the course was revised in 2006 much of the optionality was removed but there was a desire for some formal reasoning to be kept. The new course contained a half-unit called ‘Critical Thinking’. In practice this didn’t really incorporate many of the principles of the critical thinking movement and was essentially a cut down version of the old logic unit. With the advent of CfE there was an emphasis on skills and there was another attempt to link the contents of the new Arguments in Action unit with aspects of the critical thinking and informal logic. This change saw the introduction of argument diagrams. The first version of this unit lacked structure and at the first opportunity the contents were reordered and this saw the introduction of the organising principles of ‘acceptability’, ‘relevance’ and ‘sufficiency’. The most recent changes have seen the introduction of conductive arguments. There is now much in the unit that will be unfamiliar to those who have taken an introductory logic course at university for most university courses concentrate on formal logic whereas the Arguments in Action unit is more closely aligned with informal logic. Writing in 2015 Walton and Gordon identified ten characteristics of informal logic:

"We take the following ten characteristics of informal logic as our guide. (1) Informal logic recognizes the linked-convergent distinction, (2) serial arguments and (3) divergent arguments. Informal logic includes three postulates of good argument in the RSA triangle: (4) relevance, (5) premise acceptability and (6) sufficiency. (7) Informal logic has recognized the importance of pro-contra (conductive) arguments. (8) Informal logic is concerned with analyzing real arguments... There is also a ninth characteristic, (9) the appreciation of the importance of argument construction... (10) There is also a tenth characteristic, one that is very important for rhetoric, the notion of audience..."

Others have produced slightly different lists, e.g. Johnson and Blair (1980), but the essential idea is the same, whereas formal logic has given primacy to deductively valid arguments and induction has tended to be relegated as a 'problem' or something to be dealt with in the philosophy of science, informal logic is concerned with the various kinds of arguments people actually use.

Deductive arguments

|

Distinction A Deductive arguments are those whose premises are general and whose conclusion is particular, whereas Inductive arguments are those whose premises are particular and whose conclusion is general. |

|

Distinction B "A deductive argument is an argument whose conclusion follows necessarily from its basic premises. More precisely, an argument is deductive if it is impossible for its conclusion to be false while its basic premises are all true. An inductive argument, by contrast is one whose conclusion is not necessary relative to the premises: there is a certain probability that the conclusion is true if the premises are, but there is also a probability that it is false." Schaum's Outlines: Logic p23 |

|

Distinction C A deductive argument is one that makes the claim that if the premises are true, then the conclusion is guaranteed to be true. A non-deductive argument is one that makes the claim that if the premises are true, then the conclusion is likely to be true. or

Harrell p24 (emphasis added) |

Distinction A was once the traditional distinction but as long ago as 1994 George Bowles was able to describe this distinction as "almost universally discarded." There is more than one reason for rejecting this distinction but simple consistency is the most obvious. Consider the following:

Aberdeen is north of Edinburgh and Edinburgh is north of London. Therefore, Aberdeen is north of London.

Everyone wants to accept this as a deductive argument but it doesn't fit with distinction A. These kinds of counterexamples can be multiplied very easily. The SQA has made it very clear in the marking instructions for 2017 and 2018 and in the corresponding course reports that this definition will not be accepted.

The problem with distinction B is that it equates a deductive argument with a deductively valid argument. The definition of 'deductive' and 'valid' is the same. This means that it is not possible to have a 'bad' deductive argument any more than it is possible to have a bad valid argument. The distinction also means that all arguments are either deductive or inductive so any argument that isn't valid is inductive. According to this distinction the formal fallacies end up being classified as inductive arguments. In addition, it follows that the term 'invalid' cannot apply to deductive arguments and being invalid is a feature, and only a feature of, inductive arguments. Although the mandatory documents do not address this issue it is clear from past documents (e.g. the 2010 Course Specification) that the convention being followed by the Higher Course is that the valid/invalid distinction is something that applies to deductive arguments.

Distinction C is not without its problems, most notably that it isn't always possible to know what the arguer intended, nevertheless, even though it isn't clearly stated in the current mandatory documents, this is the distinction that the Higher Course has been using. The mandatory requirements for the previous version of the Higher published in 2010 stated that a deductive argument "attempts to draw certain conclusions from premises" and an inductive argument "attempts to draw probable conclusions from premises".

It is worth noting that Harrell distinguishes between deductive and non-deductive arguments rather than between deductive and inductive arguments. For more on this see inductive arguments.

Inductive arguments

To an extent the definition of inductive is determined by the definition of deductive.

The Higher Course has been using the following definition:

’Inductive reasoning attempts to draw probable conclusions from a given set of premises.’

However, it is important to be aware of some additional complications. It has been traditional to regard all reasoning as either deductive or inductive. When divided this way analogical reasoning and conductive arguments are sub-types of inductive reasoning. There is an increasing tendency, especially in the field of informal logic, to regard this binary division as unsatisfactory. Firstly, in ordinary language deductive arguments turn out to be quite uncommon and, secondly, there are then a very large number of different types of inductive arguments. Some books simply list different types of argument (e.g. deductive, inductive, analogical, conductive, etc.) and say that whatever type of argument being dealt with it is necessary to evaluate it in terms of the adequacy, relevance and sufficiency of its premises. Other books make the binary distinction between deductive and non-deductive arguments, recognising that all non-deductive arguments are attempting to establish a probable conclusion. Both of these strategies means that a different definition of inductive argument has to be given. Govier says, inductive arguments are arguments ‘in which the premises and the conclusion are empirical— having to do with observation and experience—and in which the inference to the conclusion is based on an assumption that observed regularities will persist’ (p283) and that inductive reasoning is reasoning ‘in which we extrapolate from experience to further experience.’ (p284)

Until otherwise informed it is best to use the definition that the SQA has been using to date.

The mandatory documents don't specify which types of inductive arguments should be taught. Pupils are, however, expected to recognise and evaluate arguments and to assist with this it is a beneficial to illustrate the range of inductive arguments.

|

Deductive (for comparison) I have a bag of blue marbles and have taken one out. I conclude that it will be blue. |

|

Simple induction I have a bag of marbles. I have taken ten out and they are all blue. I conclude that the next one I take out will be blue. |

|

Inductive generalisation I have a bag of marbles. I have taken ten out and they are all blue. I conclude that all the marbles in the bag are blue. |

|

Statistical syllogism I have a bag of red and blue marbles with equal numbers of each. I conclude that if I take out a handful of marbles about half of them will be blue. |

|

Statcistical generalisation I have a bag of marbles. I have taken out a handful of marbles and half of them are blue and the other half red. I conclude that the bag contains an equal number of red and blue marbles. |

The common feature of these arguments is that they extrapolate from the known to the unknown, from the observed to the unobserved. They are a special form of analogical argument in that they assume that the known and the unknown are relevantly similar so that what is true of one will be true of the other. Evaluating these arguments involves considering whether there are grounds for questioning this assumption. In particular attention can be given to sample size.

|

Abductive (Sometimes called inference to best explanation. Sometimes considered a form of induction because the conclusion is not certain; sometimes considered a separate type of reasoning.) There is a bag of blue marbles on the table and one on the floor. I conclude that the one on the floor came from the bag. |

|

Conductive (Sometimes considered a form of induction because the conclusion is not certain; sometimes considered a separate type of reasoning.) There is a bag of marbles on the table. My older sister said she would bring me some marbles; I know of nobody else who knew I wanted marbles; this type of marble is sold in a shop that is regularly used by my sister; my older sister has a key and could have let herself in. On the other hand my sister said she wouldn't be back home until tomorrow. I conclude that on balance the marbles were put there by my sister. |

Conductive Arguments.

The term ’conductive argument‘ is likely to be new to people unless they have done some reading in the field of informal logic. Nevertheless, they are very common in everyday life. Conductive arguments are always convergent, that is, they are characterised by the accumulation of evidence. Each premise gives individual support to the conclusion and that degree of individual support remains unchanged if other premises are added or removed. However, when considering the argument as a whole and evaluating the sufficiency of the premises then they are considered collectively.

When trying to determine the sufficiency of the premises it is important to take into account any other factors that might have a bearing on the issue. A distinctive feature of conductive arguments is that they allow for counter-considerations, i.e. factors that would count against the conclusion. They have sometimes been described as pro-con arguments because they involve a weighing up of the evidence.

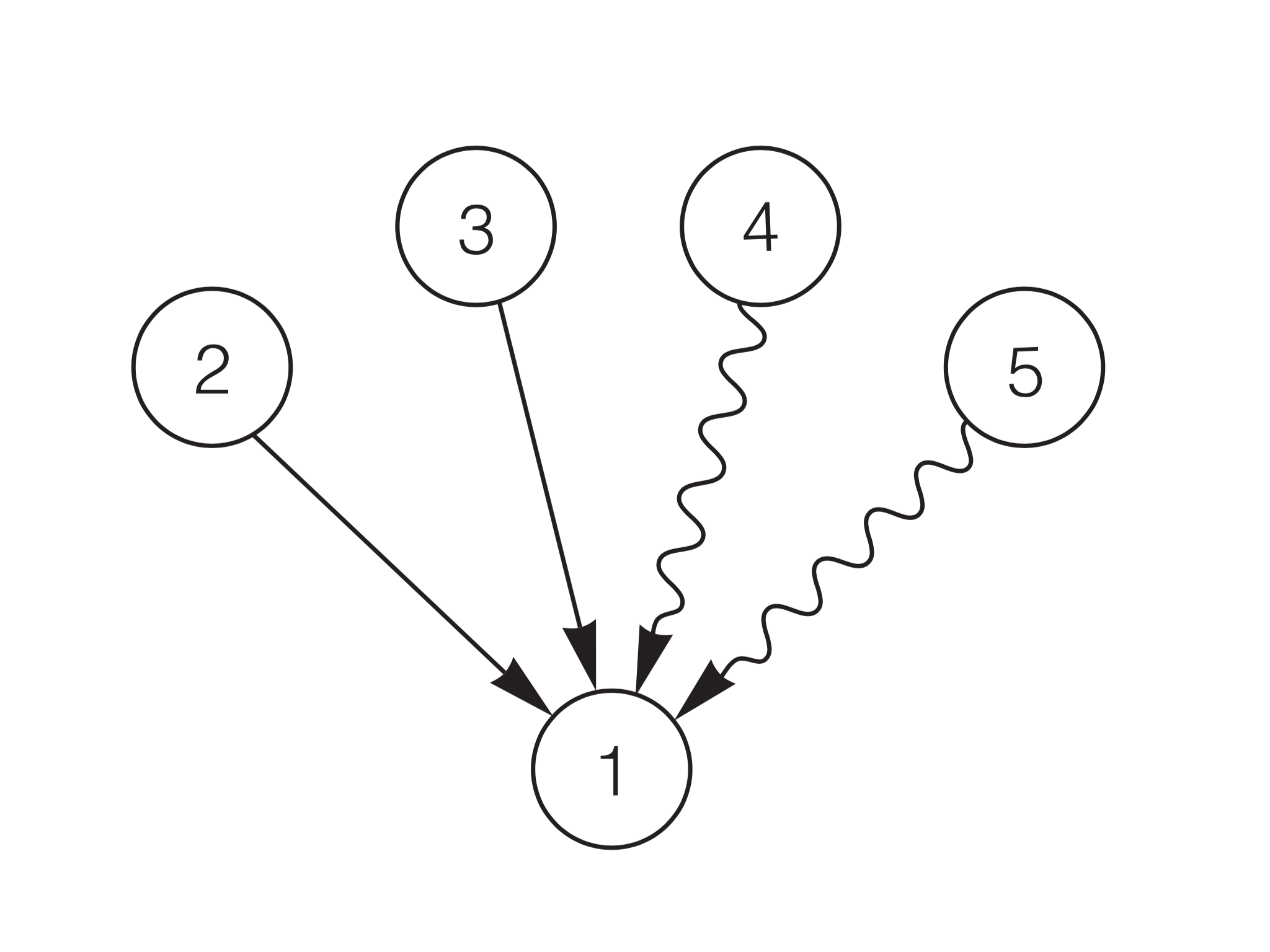

Govier diagrams conductive arguments as follows:

At the time of writing, the course guidance on argument diagrams has not been updated to reflect the inclusion of conductive arguments. As with other aspects of argument diagrams there is no agreed set of rules but the following should be noted.

- There needs to be a clear visual distinction between the premises and the counter-considerations.

- The counter-considerations are not premises. The premises offer positive support for the conclusion.

- The counter-considerations are not criticisms. If somebody else were making the same point as a way of attacking the conclusion then that would be a criticism but they are not criticisms when they are part of the weighing-up of the evidence.

‘Valid’

The definition that the course has been using over the years is the standard definition used in logic courses:

|

|

A slightly more wordy version is:

|

There are no possible circumstances where the premises are true and the conclusion is false. |

A slightly less precise definition is:

|

An argument is valid where if the premises are true then the conclusion is necessarily true. |

The reason this is less satisfactory as a definition is that it doesn’t tell you about those cases where the premises are not true.

It is important to explain to pupils that this is a technical use of the word and it differs from the everyday use of the word which means something like ‘fit for use’ as in having a valid bus ticket. The reason why this is important is because, although the technical use of the word is well established in logic courses, elsewhere the nontechnical use of the word is often applied to arguments and this has caused problems for pupils. People might say ‘that’s a valid point’ or ‘that’s a valid argument’ but be using the word in the nontechnical sense. This doesn’t mean they are wrong it is just that they are using the word in a different way in a different context.

The mandatory documents don’t address this issue and it would be helpful if they stated the definition that candidates are expected to learn. Better still, it would be good if pupils were required to know and explain how the technical use of the word differs from the more casual use of the word.

Previous versions of the Higher course made it clear that ‘valid’ and ‘invalid’ were terms that applied to deductive arguments. This is no longer the case and that is unfortunate for there are books that use the terms differently. Firstly, there is the issue that some definitions of ‘deductive’ equate deductive arguments with valid arguments which would mean there is no such thing as an invalid deductive argument. But, secondly, some books adopt the nontechnical use of the word ‘valid’ and so talk of inductively valid arguments. The following is from Logic and Contemporary Rhetoric: The Use of Reason in Everyday Life by Nancy M. Cavender, Howard Kahane.

Again, it would be helpful if the mandatory documents stated clearly what the Higher Course required.

There are two unusual consequences of the formal definition of validity that may be of interest but shouldn’t have any significant impact on the course. Consider the following two arguments:

I am in this room. I am not in this room. Therefore, the moon is made of cheese.

The world is flat. Water is dry. Therefore, two is two.

Very surprisingly, both of these are valid arguments! Recall the formal definition of validity: an argument is valid if there are no possible circumstances where the premises are true and the conclusion false. In the first of the arguments the premises are contradictory so cannot both be true. In the second, the conclusion cannot be false. So, in the first argument there are no possible circumstances where the premises are true. Since there are no possible circumstances where the premises are true it has to be the case that there are no possible circumstances where the premises are true and the conclusion false! Anything validly follows from contradictory premises. Whilst this may have some uses in formal logic it can be dismissed as a quirk of the system when dealing with everyday arguments. Interestingly, whilst technically valid they would probably be dismissed as invalid if one was using the everyday use of the word ‘valid’. It is at least a reminder that validity isn’t enough for a good argument.

‘Sound’

‘Soundness’ is no longer a mandatory concept but until recently the course has been using the following definition,

| An argument is ‘sound’ if it is valid and all its premises are true. |

This is a fairly standard definition of soundness and it relates the term to deductive arguments and not inductive arguments. Some people would say inductive arguments can never be sound; others would say it is simply inappropriate to apply the term to inductive arguments.

Some books define soundness differently. For example, E. J. Lemmon’s Beginning Logic, a classic introduction to formal logic, equates soundness with validity. It says the following:

It is probably significant that when formal logic is concerned with the manipulation of symbols it doesn’t need to pay too much attention to whether a statement is actually true or false.

Salmon in Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, which was first published in 1984 and is now into its sixth edition, applies soundness to both deductive and inductive arguments:

A similar definition is given by Bowell and Kemp in Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide which is a textbook now recommended in the Sept 2018 Course Specification.

Like validity, ‘sound’ has a non-technical use. Someone might say that the piece of wood is sound as opposed to rotten or that the building is structurally sound. Martin Hollis in Invitation to Philosophy, a classic introductory text which is still recommended reading for at least one university course seems to be equating soundness with validity when he says:

but is probably using the non-technical sense for he later says:

There are good reasons for not including soundness in the mandatory requirements. Although candidates could be asked to define soundness they could not be asked to give an example. If they were, they might write, ‘l’m sitting behind Jeevan so Jeevan is sitting in front of me.’ The examiner can assess this for validity but has no way of assessing the truth of the premise. Similarly, if the candidate is given an argument to assess for soundness it becomes a test of knowledge and to be a fair question the truth of the premises has to be so obvious the question may as well just ask for the definition. It was issues such as these that led to the 2012 question where candidates were instructed to make up a sound argument about a simple diagram:

In everyday arguments the issue isn’t whether the premises are actually true but whether they can be taken as true. This has led some writers to say that when someone says an argument is sound what they are doing is claiming that the premises are true. This is a claim that others may accept or challenge. Kaye in Critical Thinking says:

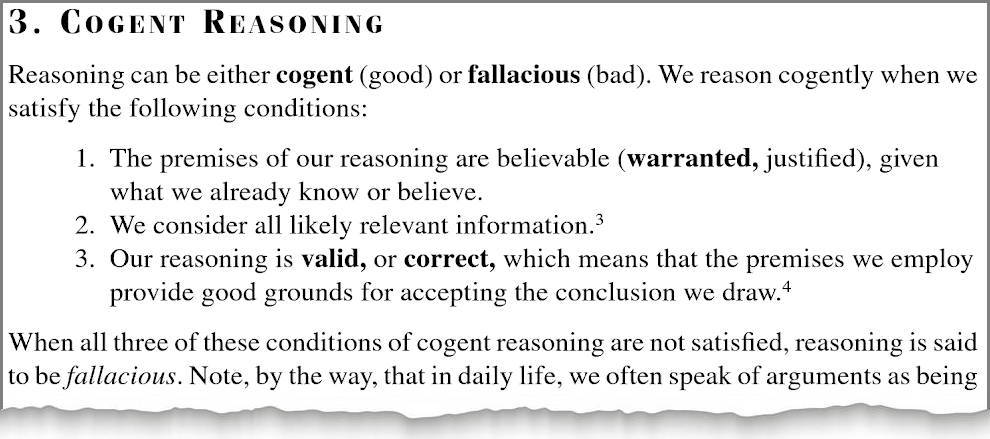

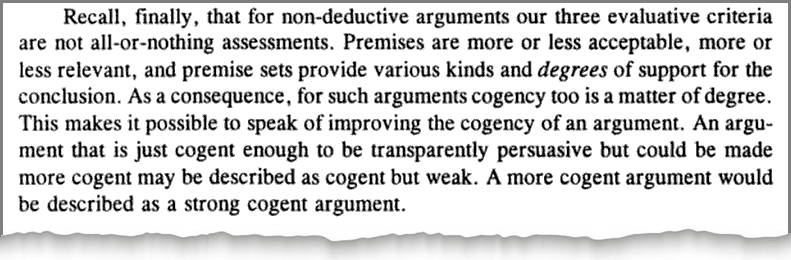

‘Cogent’

‘Cogency’ is no longer a mandatory concept. Previous versions of the Higher, where the glossary was part of the mandatory documentation, said:

| Cogency: a strong inductive argument which also has true premises is said to be cogent. |

This definition has been repeated in the more recent non-mandatory support notes. This is a reasonably widespread usage of ‘cogency’ in introductory textbooks but it does have some issues. Firstly, in assessing the truth of the premises this concept of cogency has the same issues as soundness. More importantly, the term ‘cogent’ has a wider application and unlike ‘valid’ it is not a simple matter of distinguishing between a technical use and a nontechnical use. Although a strong inductive argument with true premises would be cogent so would a sound deductive argument. To put it another way, all strong inductive arguments with true premises are cogent but not all cogent arguments are strong inductive arguments with true premises.

Perhaps the most useful definition for the Higher Course is given by Govier (p87) who says,

That is to say, a cogent argument is one where the premises are acceptable, relevant and sufficient. This is a definition given in a book that is now recommended in the 2018 Course Specification. However, it is important to repeat that, at the time of writing, the mandatory documents don’t give any specified definition of ‘cogent’ and the support notes use the more restricted use of ‘cogent’ and are silent about the wider use of the word.

A slightly different definition of cogency is given by Cavender and Kahane (p6). They say

It is important to note that in this definition they are using the nontechnical use of the word ‘valid’ and mean both deductively valid arguments and what others refer to as strong inductive arguments.

The second point is important. Consider the argument,

I’ve seen hundreds of swans and they have all been white therefore I conclude that all swans are white.

This might be punted as a strong inductive argument with a true premise. The second point would say this is not a cogent argument if the person was wilfully ignoring the fact that reliable sources of information say there are black swans but that their geographical location makes it likely that many people have never seen them.

This general approach to cogency also means that you can have inductive arguments that are weak but cogent. Bickenbach and Davies (p172) say,

Which is more reliable deductive or inductive reasoning?

Deductive reasoning aims to construct an argument such that if the premises are true then the conclusion must be true. With inductive reasoning, even if the premises are true the conclusion can be no more than highly probable. The instinctive response, then, is to say that deductive reasoning must be more reliable. However, things are not so straightforward. Consider the following two arguments:

Argument one (deductive)

All swans are white. Therefore, if there is a swan on the river it will be white.

Argument two (inductive)

Every swan I’ve ever heard about has been white. Therefore, if there is a swan on the river it will be white.

The first thing to notice is that it is possible to be much more confident about the truth of the premise in the inductive argument. Secondly, if we ask how we know that the premise in the deductive argument is true then we will presumably have to rely on:

Argument three (inductive)

Every swan I’ve ever heard about has been white. Therefore, all swans are white.

When evaluating arguments one and two any doubt about the sufficiency of the premise in the inductive argument is mirrored by doubt about the acceptability of the premise in the deductive argument.

Indeed, it is worse than that. Argument three is an inductive generalisation. There is only one situation where the conclusion is true and that is when it is a fact that all swans are indeed white. Argument two does not make a general claim. In a world where argument three has a true conclusion then so will argument two but argument two will have a true conclusion in many more situations. It could be argued, therefore, that argument two is more reliable than argument three and since the deductive argument is implicitly relying on argument three it would follow that the inductive argument (argument two) is more reliable than the deductive argument (argument one).

The only occasions when we can be confident that deductive arguments as a class are more reliable than inductive arguments is when the premises can be known to be true a priori, without relying on an associated implicit inductive argument:

Argument four

A pentagon has more sides than a square; a square has more sides than a triangle. Therefore, a pentagon has more sides than a triangle.

Slippery slopes

The slippery slope fallacy is, sorry about this, one of the more slippery fallacies. It is defined in different ways by different authors and what would be an example of a slippery slope to one author would be something else to another. The various issues are explained well on the relevant Wikipedia page which, if nothing else, distinguishes between slippery slopes and slippery slope arguments and contains a good list of the key features of a slippery slope. These are required by the Course Specification.

Counterexamples

Pupils in sixth year doing maths may come across counterexamples in that context. For example, one question might be:

When decoded this simply says

"For every 𝜒 where 𝜒 is a whole number 5𝜒 is greater than 4𝜒"

This is shown to be false by giving a counterexample, namely that when 𝜒=0 5𝜒 is not greater than 4𝜒

In Philosophy counterexamples were originally introduced because there were examples of them being used in other areas of the course. However, now they are primarily being treated as a standalone topic in the Arguments in Action component of the course. The 2018 Course Specification states:

—the use of counterexamples to show that a universal statement is false

In other words, if someone makes the claim that 'All birds can fly' a counterexample would be a bird that couldn't fly such as a penguin. Similarly, if someone makes the claim that 'Apart from humans no animal uses tools' a counter example would be a non-human animal that does use a tool. Presumably 'universal statement' will also include some statements of the form 'if p then q' but it would be helpful if this was clarified.

There is a difference between the mathematics example and the two philosophical examples. In maths the counterexample is found by trial and error and mathematical intuition; in the philosophical examples the counterexamples depend upon knowledge of the world. The challenge for question setters is to come up with questions about counterexamples that don't collapse into being a general knowledge quiz. This was avoided in the 2016 QP by asking:

Would giving a counter-example be an appropriate way to

challenge this

argument? Explain your answer.

It should be noted that philosophy books and other sources will often talk about counterexamples in the context of showing that an argument is not valid. To do this you have to provide an argument that has the same form/structure as the one that you are trying to show is invalid but in this counterexample the premises are true and the conclusion false.The ability to do this is not a stated requirement of Higher Philosophy but such counterexamples can be considered a special case of showing that a universal statement is false. When someone is claiming that their argument is valid they are effectively claiming that all arguments that have the same form/structure will be valid, i.e. they are structured such that if their premises are true then the conclusion is necessarily true. A counterexample to this universal claim would be an example of an argument that has the same form/structure but has true premises and a false conclusion. It would be helpful if it was clarified if candidates would ever be required to apply counterexamples in this way.

Descartes

It is important to be careful when selecting books on Descartes. Books are written for a number of different purposes and not all are suitable for preparing candidates for this course. In particular, quite a number of books give an abbreviated account of Descartes’ method of doubt moving from deceit of the senses onto the dream argument and then straight onto the malicious demon making no mention of the deceiving god. Others make only a cursory mention of the deceiving god as if the text says,

‘...how do I know that God has not brought it about that I too go wrong every time I add two and three or count the sides of a square, or in some even simpler matter, if that is imaginable?

But perhaps God would not have allowed me to be deceived in this way, since he is said to be supremely good.

...I will suppose therefore that not God, who is supremely good and the source of truth, but rather some malicious demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me.’

However, this misses out a large portion of text (click to view) with which candidates should be familiar.

Some books also give an overly simplified account of the trademark argument.

This is not to suggest that these books are necessarily ‘wrong’. They are being selective and writing in a way that may well be appropriate for their target audience. That audience isn’t always going to be students on this course.

Why ‘Meditations’?

The use of the word ‘Meditations’ is not just an artistic device. Descartes says,

In metaphysics...there is nothing which causes so much effort as making our perception of the primary notions clear and distinct. Admittedly, they are by their nature as evident as, or even more evident than, the primary notions which the geometers study; but they conflict with many preconceived opinions derived from the senses which we have got into the habit of holding from our earliest years, and so only those who really concentrate and meditate and withdraw their minds from corporeal things, so far as is possible, will achieve perfect knowledge of them. Indeed, if they were put forward in isolation, they could easily be denied by those who like to contradict just for the sake of it.

This is why I wrote 'Meditations' rather than 'Disputations', as the philosophers have done, or 'Theorems and Problems', as the geometers would have done. In so doing I wanted to make it clear that I would have nothing to do with anyone who was not willing to join me in meditating and giving the subject attentive consideration. For the very fact that someone braces himself to attack the truth makes him less suited to perceive it, since he will be withdrawing his consideration from the convincing arguments which support the truth in order to find counter-arguments against it.

Descartes is specifically rejecting the then standard Aristotelian method of argumentation that started from agreed premises and using syllogisms and the like worked its way to a conclusion. Instead, he is using a method, a process, to uncover undeniable foundational truths. Although parts of Meditation One can be reconstructed as an argument it is important to realise Descartes isn’t trying to put forward a traditional step by step argument such that if you follow it you will accept the conclusion. He is trying to change the way the reader thinks so that they will be compelled to recognise the truth. This explains why it is difficult to fit the malicious demon into a reconstructed argument. On the method of doubt Descartes says,

Now the best way of achieving a firm knowledge of reality is first to accustom ourselves to doubting all things, especially corporeal things. Although I had seen many ancient writings by the Academics and Sceptics on this subject, and was reluctant to reheat and serve this precooked material, I could not avoid devoting one whole Meditation to it. And I should like my readers not just to take the short time needed to go through it, but to devote several months, or at least weeks, to considering the topics dealt with, before going on to the rest of the book. If they do this they will undoubtedly be able to derive much greater benefit from what follows.

It helps to remember that the Meditations are not autobiographical. Descartes has invented a character usually referred to as the meditator. This is important because it means the conclusions that the meditator arrives at at any particular point in the Meditations may not be Descartes’ actual position. In particular, in Meditation One the meditator comes to the ‘well thought-out’ conclusion that a supremely good god could allow him to be deceived. We know this is not Descartes’ position but it is not until later in the Meditations that the view of the meditator becomes aligned with that of Descartes the author.

Various commentators have pointed out that the literary form that the Meditations takes seems to have been strongly influenced by Descartes’ Jesuit education and his undoubted familiarity with the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola.

The Malicious Demon

The Malicious Demon is often misrepresented by candidates.

|

Misrepresentation one There’s the unreliability of the senses, then the dream argument, and then, because some things have still not been brought into doubt, Descartes introduces the malicious demon to bring everything else into doubt. |

|

Misrepresentation two There’s the unreliability of the senses, then the dream argument, and then, because some things have still not been brought into doubt, Descartes introduces the idea of a deceiving god. However, because god is all good and wouldn’t deceive us he then introduces the malicious demon to bring everything else into doubt. |

To see that both of these accounts are incorrect does not require any detailed analysis of the text. All that is required is a straightforward reading of that part of the text which is often missed out.

A more accurate summary might read something like...

|

Even if everything is a dream some things cannot be doubted. However, perhaps god has created me so that I always go wrong in my beliefs about the world, beliefs about mathematics and even in simpler things. The objection that a good god wouldn’t do this fails because it is no more inconsistent for a good god to deceive me all the time than it is for god to deceive me some of the time and that clearly happens. Some might prefer to say god doesn’t exist but the less perfect my origin the more likely it is my beliefs are wrong. So, either god exists or he doesn’t (remember, that issue will not be addressed until Meditation Three). If god exists then everything is doubtful; if god doesn’t exist then everything is doubtful. Therefore, everything is doubtful. Although this is a well thought-out conclusion my old beliefs keep returning. Therefore, I will pretend there is a malicious demon... |

The demon does not introduce any fresh doubts. In particular the demon is not introduced in order to bring doubt on mathematics as that has already been done by the deceiving god. Indeed, commentators often specifically note that when talking about the demon Descartes doesn’t even mention mathematics. It is probable that nothing too significant should be drawn from this. Presumably the demon can bring doubt on everything that the deceiving god can. They are, as one writer put it, ‘epistemologically equivalent.’ What it does reinforce, though, is that Descartes’ particular concern is not with doubting reason but with showing that the senses do not provide a reliable foundation. The emphasis with both the deceiving god and the demon is on bringing the evidence of the senses into doubt:

How do I know that he (god) has not brought it about that there is no earth, no sky, no extended thing, no shape, no size, no place, while at the same time ensuring that all these things appear to me to exist just as they do now? What is more...how do I know that God has not brought it about that I too go wrong every time I add two and three or count the sides of a square, or in some even simpler matter, if that is imaginable?

I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams which he (the demon) has devised to ensnare my judgement. I shall consider myself as not having hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as falsely believing that I have all these things.

And then in the summary at the beginning of Meditation Two:

I will suppose then, that everything I see is spurious. I will believe that my memory tells me lies, and that none of the things that it reports ever happened. I have no senses. Body, shape, extension, movement and place are chimeras.

More positively, the reasons Descartes specifically gives for introducing the demon are:

- to sustain the doubts previously raised/to prevent his habitual opinions from returning

- to stop himself from believing things just because they are highly probable

- to enable himself to pretend for a time that his former opinions are utterly false

- to ensure that the distorting influence of habit no longer prevents his judgement from perceiving things correctly

A straightforward reading of the text does leave one puzzle. Having introduced the deceiving god the meditator considers the objection that a supremely good god wouldn’t deceive him. The meditator rejects this objection saying,

But if it were inconsistent with his goodness to have created me such that I am deceived all the time, it would seem equally foreign to his goodness to allow me to be deceived even occasionally; yet this last assertion cannot be made.

However, when the meditator goes on to posit the existence of the malicious demon it is introduced with the words,

I will suppose therefore that not God, who is supremely good and the source of truth, but rather some malicious demon...

We can hardly suppose that the meditator is rejecting their previous conclusion which they described as, ‘not a flippant or ill-considered conclusion, but (one) based on powerful and well thought-out reasons.’ It isn’t credible that we are to suppose the meditator is thinking, ‘Hang on a minute, I‘ve just remembered God is supremely good...’

The answer to this puzzle is to remember that these are meditations and Descartes is setting a program to help the meditator break free from their preconceived opinions and their attachment to the senses. The demon isn’t the next step of an argument, it is the next stage of the process. It is a psychological device to help the meditator think clearly.

Even so the meditator tells us ‘this is an arduous undertaking’ and they will ‘happily slide back into (their) old opinions and dread being shaken out of them.’

For someone in the grip of their preconceived opinions (and at this stage of the Meditations belief in an omnibenevolent god is still a preconceived opinion) and their attachment to the senses it is extremely difficult to break free. That is why Descartes wants his readers ‘to devote several months, or at least weeks, to considering the topics dealt with, before going on to the rest of the book.’

Descartes, scepticism & Aristotelian empiricism

It is common to read that Descartes was trying to outdo scepticism, to use sceptical arguments to prove scepticism wrong. The whole of Meditation One and the beginning of Meditation Two is presented as an attack on scepticism. This misses the point. Descartes was not particularly troubled by scepticism and didn't see it as a threat. He may have wanted to establish certainty but his target was not scepticism but Aristotelian empiricism.

It is true that Descartes presents a series of sceptical arguments which ultimately fail, or at least so Descartes claims. It is also true that the passage since has been used by philosophers to discuss scepticism. However, neither of these points establish that Descartes' intention was to attack scepticism and to prove that it was wrong.

In the synopsis he says

In the First Meditation reasons are provided which give us possible grounds for doubt about all things, especially material things, so long as we have no foundations for the sciences other than those which we have had up till now. Although the usefulness of such extensive doubt is not apparent at first sight, its greatest benefit lies in

- freeing us from all our preconceived opinions, and

- providing the easiest route by which the mind may be led away from the senses.

The eventual result of this doubt is to

- make it impossible for us to have any further doubts about what we subsequently discover to be true.

Descartes' focus, what he is attacking, is a reliance on preconceived opinions and the evidence of the senses which he regards as inadequate. Yes, Descartes wants to claim that his own position is immune to 'further doubts' but that is not because he wants to prove scepticism wrong, it is because he wants to show that his position is superior to the empiricist position.

It is true that at the beginning of Meditation II Descartes has the meditator say,

Archimedes used to demand just one firm and immovable point in order to shift the entire earth; so I too can hope for great things if I manage to find just one thing, however slight, that is certain and unshakeable.

But who is this meditator? The first person narrator is not some kind of sceptic who is learning the error of their ways. The narrator, the meditator, is someone who is and has been in thrall to their preconceived opinions, who has relied on the evidence of their senses. Throughout Meditation One the emphasis is on doubting the senses. Even when the meditator considers the possibility of a deceiving God, before he mentions mathematics, he says:

How do I know that he has not brought it about that there is no earth, no sky, no extended thing, no shape, no size, no place, while at the same time ensuring that all these things appear to me to exist just as they do now?

When he introduces the malicious demon there is no mention of mathematics and, once again, the emphasis is on material things

I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams which he has devised to ensnare my judgement. I shall consider myself as not having hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as falsely believing that I have all these things.

None of this should be surprising. Recall that in the synopsis he said he wanted to raise 'grounds for doubt about all things, especially material things.'

Writing to Mersenne, Descartes says that the various headings of the six meditations are what he wanted people to mainly notice but adds,

But I think I included many other things besides; and I may tell you, between ourselves, that these six Meditations contain all the foundations of my physics. But please do not tell people, for that might make it harder for supporters of Aristotle to approve them. I hope that readers will gradually get used to my principles, and recognize their truth, before they notice that they destroy the principles of Aristotle.

When he refers to 'the principles of Aristotle' he may have been referring to more than just Aristotelian empiricism but it presumably includes his empiricism. Remember it was the Aristotelian approach that was summed up in the scholastic maxim, "There is nothing in the intellect that was not first in the senses."

When commenting on the sceptical arguments in the Replies Descartes is dismissive of them, referring to them as reheated leftovers:

Now the best way of achieving a firm knowledge of reality is first to accustom ourselves to doubting all things, especially corporeal things. Although I had seen many ancient writings by the Academics and Sceptics on this subject, and was reluctant to reheat and serve this precooked material, I could not avoid devoting one whole Meditation to it. And I should like my readers not just to take the short time needed to go through it, but to devote several months, or at least weeks, to considering the topics dealt with, before going on to the rest of the book. If they do this they will undoubtedly be able to derive much greater benefit from what follows.

The purpose of doing so is not because scepticism needs to be refuted but because:

All our ideas of what belongs to the mind have up till now been very confused and mixed up with the ideas of things that can be perceived by the senses. This is the first and most important reason for our inability to understand with sufficient clarity the customary assertions about the soul and God.

It is often pointed out that Descartes didn't doubt everything. In the Principles Descartes says:

…when I said that the proposition I am thinking, therefore I exist is the first and most certain of all to occur to anyone who philosophizes in an orderly way, I did not in saying that deny that one must first know what thought, existence and certainty are, and that it is impossible that that which thinks should not exist, and so forth. But because these are very simple notions, and ones which on their own provide us with no knowledge of anything that exists, I did not think they needed to be listed.

Nor, in the Meditations, is it obvious that Descartes clearly doubts his ability to reason reliably, particularly after establishing the cogito. If this were a general attack on scepticism this would be a serious criticism but its absence makes perfect sense if the work is understood to be concerned much more about getting the Aristotelian empiricists to change their way of thinking.

When it was pointed out to Descartes that Augustine had used a very similar argument to his cogito to refute scepticism Descartes replies that to infer existence from the fact one is doubting could have occurred to anyone but he was using the cogito for an entirely different purpose.

TO COLVIUS, 14 NOVEMBER 1640

I am obliged to you for drawing my attention to the passage of St Augustine relevant to my I am thinking, therefore I exist. I went today to the library of this town [Leiden] to read it, and I do indeed find that he does use it to prove the certainty of our existence. He goes on to show that there is a certain likeness of the Trinity in us, in that we exist, we know that we exist, and we love the existence and the knowledge we have. I, on the other hand, use the argument to show that this I which is thinking is an immaterial substance with no bodily element. These are two very different things. In itself it is such a simple and natural thing to infer that one exists from the fact that one is doubting that it could have occurred to any writer. But I am very glad to find myself in agreement with St Augustine, if only to hush the little minds who have tried to find fault with the principle.

We should not go overboard in saying that Descartes was not trying to defeat the sceptics. He was trying to establish something certain and when challenged in the Objections about whether he had taken his method too far and whether it had achieved anything he does reply:

...he did not in fact have any reason to suspect that I had gone astray in any of my assertions, or in the arguments by means of which I became the first philosopher ever to overturn the doubt of the sceptics

There are elements of Meditation One that mirror Montaigne's writing and so, given where Descartes ends up, might be taken as a refutation of Montaigne's scepticism. However, it doesn't seem that this is the primary purpose of Descartes' sceptical method. At the time various groups would use sceptical arguments to challenge their opponents and it appears to be something like this that Descartes is doing. He is using scepticism but addressing the Aristotelians. Responding to objections to the Discourse, Descartes says,

"I agree...that I have not adequately presented the arguments by which I think I prove that there is nothing that, in itself, is more evident and certain than the existence of God and of the human soul. However, I did not dare to attempt this, because I would have had to explain at length the strongest arguments of the sceptics to show that there is no material thing of whose existence one is certain."

In the Discourse Descartes was reluctant to explain the strongest arguments of the sceptics because, "if weak minds avidly embraced the doubts and scruples that I would have had to propose, they might not be able to understand as fully the arguments by which I tried to remove them."

Where Descartes might more clearly be responding to the threat of scepticism is in his rehabilitation of the external world later on in the Meditations. However, the establishment of certainty is always in the context of rejecting the senses as the most reliable means of gaining knowledge. At the end of the synopsis Descartes says of Meditation Six:

...lastly, there is a presentation of all the arguments which enable the existence of material things to be inferred. The great benefit of these arguments is not, in my view, that they prove what they establish — namely that there really is a world, and that human beings have bodies and so on — since no sane person has ever seriously doubted these things. The point is that in considering these arguments we come to realize that they are not as solid or as transparent as the arguments which lead us to knowledge of our own minds and of God, so that the latter are the most certain and evident of all possible objects of knowledge for the human intellect. Indeed, this is the one thing that I set myself to prove in these Meditations.

The problem with three waves.

The metaphor of something arriving in waves is, unfortunately, only too familiar. Its effectiveness as an image means that it has not only been applied to pandemics but many other things. It is not surprising that it has also been applied to Descartes' method of doubt. A quick search shows that there are many web pages and assorted text books that refer to Descartes' three waves of doubt. This may, at least in part, be because it has been given quasi-official status by being specifically included in the AQA's A and AS level syllabus and specimen question paper:

This is unfortunate because it is a decidedly problematic way of describing Descartes' text. For one thing there seems to be a correlation between those sources describing Descartes' 'three waves' and those that skate over the deceiving God or conflate the deceiving God with the malicious demon. Apart from that, it is not at all obvious that there are just three waves.

It is difficult to identify who introduced the notion of Descartes' 'three waves of doubt'. In any case, since it is such a common metaphor, it is entirely possible that it was introduced independently by more than one writer.

One contender is John Cottingham. In 'Rationalism' published in 1984 Cottingham writes:

Descartes' doubt comes in three waves.

- First, the testimony of the senses is rejected...

- Next, even judgements about present experience are rejected... The scope of this argument (the dreaming argument' as it has come to be known) is extended to cast doubt on any judgement whatsoever which I may make about the external world; however, it does not impugn the truths of logic and it does not impugn the truths of logic and mathematics...

- But now the third and most devastating wave of doubt arises. Suppose there is a deceiving God who systematically makes me go wrong whenever I add two and three or count the sides of a square. If there is such a 'malignant demon' - and I cannot so far disprove this possibility then absolutely nothing seems free from doubt...

As you can see, in this passage Cottingham has three waves and runs together the deceiving God and the 'malignant demon'. Given Cottingham's status as a scholar perhaps that should be the end of the matter. Unfortunately, things are not so straightforward. In his 1988 book, 'The Rationalists', Cottingham writes:

Descartes's doubt comes in four successive waves, and each succeeding wave is designed to demolish an apparently secure area left standing by the preceding wave.

- First, we are reminded that the senses sometimes deceive us (sense-based judgements such as 'that tower is round' can turn out, on closer scrutiny, to be mistaken); and 'it is prudent never to trust completely those who have deceived us even once'.

- The argument so far has left unscathed a large number of seemingly quite unproblematic sense-based judgements such as 'I am holding my hand in front of my face'; these, it seems, I would be mad to doubt. But now the second wave of doubt arrives: it is possible that even the judgement that I am holding my hand up could be false; for I might at this very moment be dreaming--not holding my hand up before my eyes, but asleep in bed with my eyes closed.

- The possibility that I am now dreaming leaves unscathed my belief in the existenoe of at least general kinds of things such as heads, hands, and faces (for though a particular judgement about this hand may be false if I am dreaming, dreams are presumably formed from ingredients taken from real life). But now the third wave of doubt arrives: a dream may be compared to an imaginative painting--and though some paintings are formed by rearranging ingredients taken from real objects, it seems possible that a painting could depict 'something so new that nothing remotely similar has even been seen before-- something which is therefore completely fictitious and unreal'. Could it not be, then, that my dreams have no foundation in reality whatever? (Later this doubt is reinforced by the scenario of a malicious demon who has brought it about that 'the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams which he has devised to ensnare my judgement'.)

- Despite the disturbingly radical implications of the doubt so far raised, Descartes notes that it nevertheless leaves unscathed at least his grasp of what he calls 'simple universals' such as extension, size, quantity, and number. These general categories appear unaffected by the possibility of wholesale deception about the external world; and they seem to provide the basis for reliable mathematical judgements that can be made regardless of what exists around me. For 'whether I am awake or asleep two and three added together are five, and a square has no more than four sides; and it seems impossible that such transparent truths should incur any suspicion of being false'. But now the final and most devastating wave of doubt arrives. If, as I have been taught, there is an omnipotent God, it may be, for all I know, that he makes me go wrong 'every time I add two and three or count the sides of a square'; while if, on the other hand, my existence is not due to God but to some random chain of lesser causes, then it seems even more likely that I am so imperfect as to go astray even in my intuition of the simplest and seemingly most transparent truths.

So now we have four waves of doubt. The second and third are both associated with dreaming and the fourth is a combination of a God who might be making me go wrong and the possibility of me having an unreliable origin which results in me going astray.

The idea of four waves is also seen in the earlier article by Hiram Caton (The Theological Import of Cartesian Doubt,International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Winter, 1970). Caton somewhat poetically writes:

The drama is so pronounced that it is possible to discern something like a plot line. A solitary wayfarer sets out on a spiritual journey to discover certain knowledge. After three waves of doubt, he finds what at first appears to be terra firma, only to be overwhelmed by dark thoughts about his "author." In order to escape this condition, by an act of will he imagines the worst possible condition - his author is a malignant and omnipotent demon. By dint of his own efforts he triumphs over the evil demon in the self-certitude of the cogito. From this Archimedian point he gradually emerges from the wilderness of doubt.

Here we have three waves of doubt, which will be the unreliable senses and the two dreaming doubts, followed by the tentative conclusion, before being 'overwhelmed' by a fourth wave which is doubts concerning his 'author', whether that be God or something lesser, before finally moving on to the evil demon.

Returning to Cottingham, in his book 'Descartes' first published in 1986, he says,

"Descartes dramatic presentation of the successive waves of doubt that engulf him may be divided for convenience into twelve phases."

To be clear, Cottingham hasn't suddenly discovered twelve doubts, rather these phases are a useful summary of the to and fro of Meditation One. However, of the twelve points, five might be classified as doubts and then as a sixth the demon is put forward as a means of sustaining these doubts.

From the above I think it is clear that it is both unhelpful and misleading to teach that Descartes' has 'three waves of doubt'. For candidates who need to be familiar with the text, Cottingham's twelve phases is much better. Alternatively, since it is important to grasp that Descartes has created a first person narrator who is on a philosophical journey, Larmore's presentation of the material as dialogue between an empiricist narrator and a sceptic challenger is also helpful. Both of these summaries can be found here.

The Trademark Argument

It is perfectly possible to start an exploration of Meditation One by reading the text. Although some of the ideas turn out to be a little more complicated than they first appear it is an easy enough read. The same is not true for Meditation Three. Descartes is using concepts that are entirely alien to 21st century thinking. For that reason it is necessary to begin by explaining the concepts and then see how they appear in the text.

For what it's worth, I don't think the Trademark Argument is too difficult for Higher candidates. It has been in the course for a while, it is in the A-level course and there are school-level texts available. However, this is now a text-based unit and candidates are expected to have an in-depth knowledge of the text. Given its complexity, asking Higher candidates to have an in-depth knowledge of the whole of Meditation Three is a very big ask. The documentation does now say, 'The following text extracts from Descartes are prescribed. The course specification lists aspects of the text which candidates must study in detail.' Based on this instruction very little of the second half of Meditation Three needs to be looked at but it would be good to have that confirmed. Much better would be if the prescribed text of Meditation Three could be cut down to just those bits that do need to be looked at in detail. It isn't helpful to have a prescribed text parts of which don't need to be looked at or a text that needs to be looked at in-depth in some vaguely specified parts and in less depth in other parts.

It is understandable that teachers can be ambivalent about Wikipedia and recommending a page can lead to problems when the page later gets updated. Here I have used a permanent link to a particular revision of the page. For those struggling to find information about the Trademark Argument this is a very helpful page. It gives the necessary background about degrees of reality and formal and objective reality. It also gives some helpful criticisms of the Trademark Argument.

There are two other common criticisms that are worth commenting on.

- A spark setting off a forest fire is said to contradict the causal adequacy principle. This criticism lacks initial plausibility. Descartes will have been very familiar with embers being used to start a fire and it is very difficult to understand how Descartes or any of his interlocutors in the Objections would have missed such an obvious criticism. It is also difficult to understand why it would have taken 350 years before such a criticism was spotted. As the Wikipedia page notes, degrees of reality are not related to size. An elephant does not have more reality than a goldfish. Under Descartes' scheme they would both have the degree of reality associated with finite substances. There is nothing in Descartes' scheme to suggest a spark would not be able to start a forest fire.

- The sponginess of a sponge cake emerging from the ingredients. This criticism is much more interesting coming as it does from John Cottingham one of the foremost scholars on Descartes. For that reason alone I am sure it will continue to be accepted. It is, however, something of a puzzle for under Descartes’ scheme the sponginess is presumably a property or a mode (which would have the lowest level of reality) and there is nothing within the scheme to say that a finite substance (which has a higher level of reality) cannot in some way be responsible for the existence of a mode which is dependent on that substance. Furthermore, this is again something with which Descartes would have been entirely familiar. Descartes had even thought deeply about such things. In Meditation Two his wax example depends upon the complete transformation of the physical properties of the wax. It is important to note that Cottingham does not offer this example as an immediate criticism of Descartes. Rather it is in response to a modified version of the causal adequacy principle suggested by Gassendi. So, the sponginess is offered as a counter-example to a causal adequacy principle based on material causation. [One might say that a chain gets its strength from the strength of its component links but the cake does not get its sponginess from the sponginess of its component ingredients.] However, Descartes version of what came to be called the causal adequacy principle is concerned with the 'efficient and total' cause. It is not that the sponginess is a counterexample which shows Descartes' scheme to be obviously wrong, it is more that explaining the sponginess leads to more problems further down the line. Descartes says:

"A stone, for example, which previously did not exist, cannot begin to exist unless it is produced by something which contains, either formally or eminently everything to be found in the stone9; similarly, heat cannot be produced in an object which was not previously hot, except by something of at least the same order <degree or kind> of perfection as heat, and so on."

[9‘... i.e. it will contain in itself the same things as are in the stone or other more excellent things’ (added in French version). In scholastic terminology, to possess a property ‘formally’ is to possess it literally, in accordance with its definition; to possess it ‘eminently’ is to possess it in some higher form.]

Descartes needs the notion of that which is caused to be produced by something which contains everything about it possibly eminently rather than formally because he needs to explain how a non-physical God can produce the physical universe. The physical aspect of the universe exists eminently within God. With regard to the sponge cake it would seem that Descartes is committed to saying the sponginess exists eminently within the ingredients or, pushing back further, in whatever was responsible for the ingredients. This leads to two difficulties:

- As Cottingham says, it makes the causal adequacy principle trivially true. It ends up as if you are saying that when something exists eminently in that which produced it you are effectively saying that what produced it is such that it is capable of producing it. True, but trivial.

- When it comes to ideas, and particularly the idea of God, Descartes wants to say: 'although one idea may perhaps originate from another, there cannot be an infinite regress here; eventually one must reach a primary idea, the cause of which will be like an archetype which contains formally <and in fact> all the reality <or perfection> which is present only objectively <or representatively> in the idea.' He later says, 'It is true that I have the idea of substance in me in virtue of the fact that I am a substance; but this would not account for my having the idea of an infinite substance, when I am finite, unless this idea proceeded from some substance which really was infinite'. The sponginess doesn't have to be produced by something that really is spongy but the idea of God must be produced by something that really is God. This seems inconsistent.

In response to the second point I can imagine Descartes saying that the two situations are not comparable for in the case of sponginess, when looking for the efficient and total cause, you can push back beyond the ingredients to something that does contain the sponginess eminently but in the case of God you cannot push back any further so it does have to be the reality of God that is the source of your idea.

Needless to say, this level of analysis goes way beyond what I would be expecting of a Higher candidate. With regard to the two criticisms the first seems to miss the point and is best avoided. The second is either likely to be presented in a way that is attacking a position that wasn't Descartes' or will be too subtle for any but the best candidates to get right.

Clear and distinct perception

Hume

Resources found helpful In preparing to study Hume’s Enquiry.

Utilitarianism

Resources found helpful in preparing for the study of utilitarianism.

Hedonic calculus

The Hedonic Calculus is a pseudo-mathematical process proposed by Bentham for calculating the sum total of pleasure or pain that would result from any action. The first four criteria [intensity; duration; certainty or uncertainty; propinquity or remoteness] are properties of the pleasure or pain. The next two [fecundity and purity] are properties of the action and are concerned with its tendency to produce more of the same or more of the opposite. The final criterion [extent] is not just a matter of counting up the number of people who are affected positively and negatively. Bentham says the first six criteria should be used to calculate the balance of pleasure and pain and that this process should then be applied to each person affected in order to arrive at the general tendency of the act whether for good or ill. Bentham says that ‘it is not to be expected that this process should be strictly pursued previously to every moral judgment, or to every legislative or judicial operation’ but should always kept in view.

The greatest happiness of the greatest number

This is one of the most famous slogans in all philosophy. The problem is that it doesn’t accurately represent classical utilitarianism and was ultimately rejected by Bentham because it was misleading. It continues to mislead pupils today.

In an early work (A Fragment on Government, 1776) Bentham says, ‘it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong’ and he described this as a ‘fundamental axiom’. However, the phrase then disappears from his writings. There is some academic debate as to why this is but it seems that Bentham was trying to formulate his fundamental axiom in a way that wouldn’t cause problems. In 1829 he wrote,

Greatest happiness of the greatest number. Some years have now elapsed since upon a closer scrutiny, reason, altogether incontestable was found for discarding this appendage.

Bentham rejected the wording because it would give licence to the majority to increase their happiness to the detriment of the minority. He gives as possible examples the Catholic minority in Great Britain and the Protestant minority in Ireland. The wording also leads to a conflict with the principle of maximising happiness.

The problem can be explained like this. Imagine there are three people and two possible courses of action, A & B. The amount of happiness that each course of action would produce is indicated by the number of As and Bs.

Person one: AAB

Person two: AAB

Person three: ABBBB

The greatest happiness for person one is achieved by following the A course of action. The greatest happiness for person two is also achieved by following the A course of action. The greatest happiness for person three is achieved by following the B course of action. So, the greatest happiness for the greatest number is achieved by following the A course of action. However, happiness is maximised by following the B course of action.

It is common for pupils to think that if it makes more people happier then utilitarianism says that is what you must do. Given that Bentham rejected the slogan for precisely this reason it is clearly an inaccurate characterisation of utilitarianism. It may be that doing the right thing will make the majority happier but it isn’t this that makes it the right thing to do. This misunderstanding is usually compounded by a misunderstanding of what Bentham means by ‘extent’ in the hedonic calculus.

Perhaps the best way to avoid these errors is to specifically explain why Bentham rejected the slogan.

The Act Utilitarian Use of Rules.

Act utilitarianism teaches that an act is right if it maximises happiness. Rule utilitarianism teaches than act is right if it conforms to a rule which is in place because having that rule maximises happiness even if on this particular occasion happiness isn’t maximised. In other words act and rule utilitarianism are theories that tell you why something is right. It is important to distinguish this from any decision making procedure that a utilitarian might use. It is important to remember that act utilitarians nearly always advocate the use of rules as way of helping people to do the right thing.

|

Act-consequentialism is best conceived of as maintaining merely the following: Act-consequentialist criterion of wrongness: An act is wrong if and only if it results in less good than would have resulted from some available alternative act. When confronted with that criterion of moral wrongness, many people naturally assume that the way to decide what to do is to apply the criterion, i.e., Act-consequentialist moral decision procedure: On each occasion, an agent should decide what to do by calculating which act would produce the most good. However, consequentialists nearly never defend this act-consequentialist decision procedure as a general and typical way of making moral decisions… There are a number of compelling consequentialist reasons why the act-consequentialist decision procedure would be counter-productive… …most philosophers accept that, for all four of the reasons above, using an act-consequentialist decision procedure would not maximize the good. Hence even philosophers who espouse the act-consequentialist criterion of moral wrongness reject the act-consequentialist moral decision procedure… https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consequentialism-rule/ |

Bentham, having explained the hedonic calculus, finishes off by saying,

It is not to be expected that this process should be strictly pursued previously to every moral judgment, or to every legislative or judicial operation. It may, however, be always kept in view: and as near as the process actually pursued on these occasions approaches to it, so near will such process approach to the character of an exact one.

Even Bentham doesn’t expect the calculation to be carried out every time. What is important is doing the right thing not the specifics of how you make your decision. It is noteworthy that here Bentham specifically links the hedonic calculus to legislative procedures, i.e. to the formulation of rules, and Bentham will certainly have expected people to follow the law, but this doesn’t make Bentham a rule utilitarian.

Assuming that Mill is best described as an act utilitarian who is advocating the use of rules, he says,

It is truly a whimsical supposition that, if mankind were agreed in considering utility to be the test of morality, they would remain without any agreement as to what is useful, and would take no measures for having their notions on the subject taught to the young, and enforced by law and opinion… to consider the rules of morality as improvable, is one thing; to pass over the intermediate generalisations entirely, and endeavour to test each individual action directly by the first principle, is another… The proposition that happiness is the end and aim of morality, does not mean that no road ought to be laid down to that goal… Nobody argues that the art of navigation is not founded on astronomy, because sailors cannot wait to calculate the Nautical Almanack. Being rational creatures, they go to sea with it ready calculated; and all rational creatures go out upon the sea of life with their minds made up on the common questions of right and wrong.

Act utilitarianism is a living philosophy and different (act) utilitarians will take different positions on when and under what circumstances these rules should be broken.

A common misrepresentation.

There are some very common misrepresentations of utilitarianism. Perhaps the most persistent is that (act) utilitarians have no respect for the law. The story usually goes something like this...A rich person drops a twenty pound note and it is picked up by a poor person. Should the poor person return the money or keep it to buy food? People who have only a very superficial understanding of utilitarianism tend to say that act utilitarians would say the right thing to do is for the poor person to keep the money. The problem is that this assumes the law is completely irrelevant to act utilitarians. Ironically, this is often said by the same people who have just said that Bentham is an act utilitarian obviously completely unaware that the hedonic calculus is taken from Bentham’s book ‘Principles of Morals and Legislation’.

The key to understanding why utilitarians don’t advocate breaking the law is to remember that they are concerned with the long term consequences as well as the short term consequences.

In The Theory of Legislation Bentham specifically addressed this kind of situation. He says,

It is true there are cases in which, if we confine ourselves to the effects of the first order, the good will have an incontestable preponderance over the evil. Were the offence considered only under this point of view, it would not be easy to assign any good reasons to justify the rigour of the laws. Every thing depends upon the evil of the second order; it is this which gives to such actions the character of crime, and which makes punishment necessary. Let us take, for example, the physical desire of satisfying hunger. Let a beggar, pressed by hunger, steal from a rich man's house a loaf, which perhaps saves him from starving, can it be possible to compare the good which the thief acquires for himself, with the evil which the rich man suffers? … It is not on account of the evil of the first order that it is necessary to erect these actions into offences, but on account of the evil of the second order.

When Bentham talks of evils of the second order he is referring to the long term consequences of allowing or advocating that people break the law. There is, of course, a debate between utilitarians themselves as to when it is legitimate to break the law, as to when civil disobedience might be permitted, or even when rebellion is called for, but it is wrong to suggest that utilitarians have no respect for the law or that they would encourage people to break the law to gain some short term benefit.

Strong and weak rule utilitarianism.

These terms are found in some school level textbooks but don't seem to appear in any academic works. Of course, the fact that I haven't been able to track them down doesn't mean they don't exist and I would welcome information that proves me wrong.